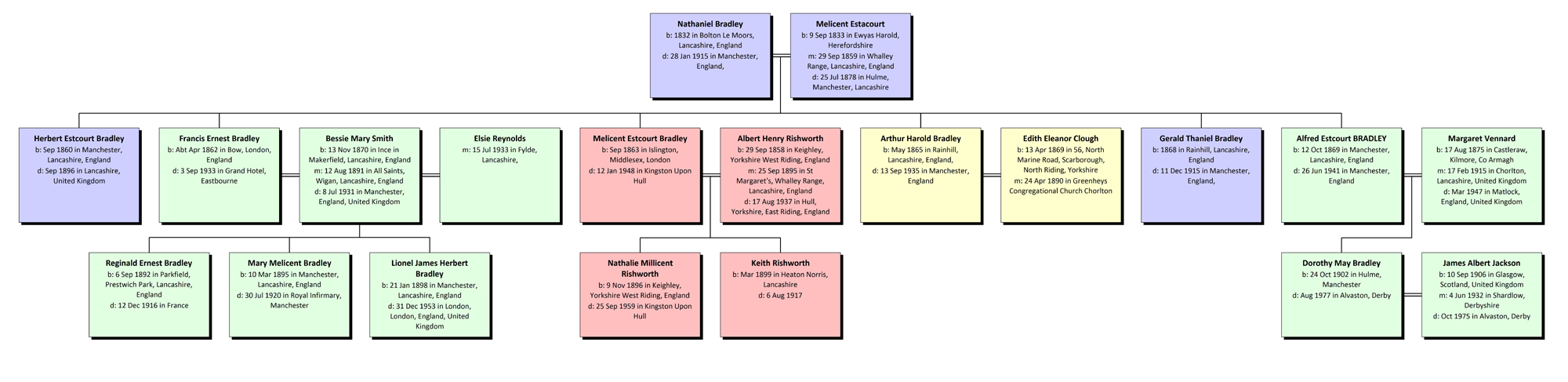

Lionel Bradley (1898–1953): A Family History and Biography

For much of his adult life Lionel Bradley was a librarian of some distinction, at Liverpool University, and later at the London Library, but posthumously he is best remembered as a remarkable chronicler of the performing arts, first in the north-west of England, and later in London. I have given a partial account of that part of his life elsewhere,((See Lionel Bradley: One Man’s Britten; also the BBC radio documentary One Man’s War (2012).)) but this essay seeks to document his family background and career.

The Family – Paternal grand-parents

Lionel Bradley was a member of a large, mainly Lancashire family that was upwardly mobile during the nineteenth century. On the paternal side, one great-grandfather, Robert Bradley (born c.1801) was a cotton weaver at Bolton in 1841, but Robert’s only son, Nathaniel (1832–1915) did not follow this trade, but instead enlisted as an Inland Revenue and Excise Officer, serving as an investigator in various prosecutions reported in the local press in the 1850s.((E.g. Manchester Courier, 23 May 1857, p. 8; ibid., 30 April 1859, p. 9.)) However, his work with the Excise clearly fostered an interest and training in chemistry, and by 1862 Nathaniel had moved to London as analytical chemist to the Board of Inland Revenue.((Manchester Courier, 2 August 1862, p. 6).)) How long this appointment lasted is unclear, but by 1871 he was again living in Manchester (where he was fined for illegal use of corporation water to power a steam-driven washing machine!),((Manchester Evening News, 14 November 1871, p. 2)) joined the Royal Society of Chemists in 1876((E-mail communication from David Allen, Library Collections Coordinator Royal Society of Chemistry, 22 July 2010. In Slater’s Directory for 1876 Bradley is still listed as an Inland Revenue Officer, living at 51 Chapman Street, Manchester.)) and afterwards established himself as a self-employed ‘Consulting and Analytic Chemist’ and businessman in the city.((See Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory of Manchester and Salford (Manchester: Issac Slater, 1878-9), part II, p. 12; 1881 Census (Class: RG11; Piece: 3927; Folio: 94; Page: 9; GSU roll: 1341938). ))

On 29 September 1859 Nathaniel married Melicant Estcourt (or Estacourt) (1833–1878) at Whalley Range, Lancashire; she was the daughter of another exciseman, Thomas Estcourt (or Estacourt) (c.1801–1879) who was living, by then, in Hulme.((See the relevant census records. A comprehensive family tree can be consulted online, but a subscription will be required.)) Apart from the marriage, it was brewing that provided a strong link between the Bradley and Estcourt families through Estcourt & Co. It is not clear who founded this firm, or when, but by the early 1870s Nathaniel had joined as a partner and through it the two men traded as ‘brewers, analytical chemists and manufacturers’.((See Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 4 December 1874, p. 8, an article that provides much information about the Estcourt family.)) After Thomas’s death Nathaniel seems to have run the firm on his own and by 1886 it occupied the same premises (53/55 Chapman Street, Hulme) as Bradley’s own chemical analysis and chemical manufacturing (brewer’s requisites) business. In the 1890s Estcourt & Co. advertised itself as an analytical chemist and manufacturer of ‘Hop supplement, Yeast nourishment and Frothing powder.’((Slater’s Manchester and Salford Directory for 1895 (Manchester: Slater’s Directory Ltd., 1895), part II, pp. 8, 51, 52.))

Two of Melicant’s brothers also had connections with brewing. Charles (1837–1921), trained as a chemist in Bristol, and worked as an agent for Estcourt & Co. (1871–3) before followed their father into the Excise service, then setting up as a self-employed analytical chemist and finally in the late 1870s becoming the City Analyst for Manchester.((As several references in the British Medical Journal reveal, by the 1870s he was a FCS and FIC, although by the end of the century his techniques were subject to some criticism.)) Another of Melicant’s brothers, Frederick Edmund (1839–1910) worked for some years in Manchester as a clerk (c. 1861–73), was briefly a partner in a shipping business((See London Gazette, 15 July 1884, p. 3242, for the termination of the partnership.)) and then in a firm involved in ale and porter brewing and the wine and spirit trade.((See London Gazette, 18 October 1889, p. 5742, for the termination of the partnership.)) By 1891 he described himself as a ‘Manufacturing Chemist of Brewer’s Requisites and Hop Agent’,((1891 Census, Class: RG12; Piece: 3163; Folio 12; Page 17; GSU roll: 6098273.)) but by 1901 he was working as an agent for a whisky distillery.((1901 Census, Class: RG13; Piece: 3975; Folio: 79; Page: 35.))

This account of Charles and Frederick Estcourt’s professional lives suggests solid middle-class careers, but in other respects the male members of this generation of the family were dysfunctional, as was revealed in the press reports of an injunction sought by (and granted to) Thomas Estcourt and Nathaniel Bradley against Charles, Frederick and their younger brother, Henry (1844–1900) along with several others who, it was alleged, had conspired to obtain the secret formula for Estcourt’s Hop Supplement, a compound widely used in brewing and the sole property of Estcourt and Co. This the defendants allegedly then manufactured and distributed as purporting to have been supplied by Estcourt and Co. On 3 December 1874 at the Court of Chancery the Vice Chancellor Richard Malins found for the plaintiffs but commented that ‘it was deplorable that a family should tear itself to pieces in the manner which the Estcourts had adopted’.((See Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 4 December 1874, p. 8.)) No further references to this legal process have been found, so presumably some sort of resolution must have been achieved, but no doubt the fact that it was Nathaniel – related only by marriage – who had been offered a partnership by Thomas must have rankled with his sons.((For Henry Estcourt, who was apparently not a prime mover in the deception, a further encounter with the courts was to follow. After qualifying as a surgeon (MRCS in 1867), and establishing himself in the profession, in 1891 he was convicted of ‘conspiring with another by divers false pretences to cheat and defraud’, and sentenced to 21 month’s imprisonment (see England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 National Archives Series Ho26 and HO27).))

Nathaniel and Melicant had at least six children, of whom the second recorded, Francis Ernest was to be Lionel Bradley’s father. The first, Herbert Estcourt Bradley (1860–1896) seems to have had a difficult business career: sometime after 1886 in Manchester he formed a partnership with a Henry Labrey Rooke in a firm of grey cloth merchants trading under the name of Bradley and Rooke, but on 12 April 1889 this partnership was dissolved, with Bradley carrying on the business (and shouldering the debts).((See the London Gazette, 16 April 1889, p. 2183. There is no entry for Bradley & Rooke in Slater’s 1886 Directory of Manchester.)) The 3 May issue of The London Gazette includes a notice of the dissolution of another partnership – this time with his father, Nathaniel – in a grey cloth merchants called N. Bradley & Sons operating from the same address as that previously associated with Bradley & Rooke.((The dissolution of the partnership was also reported in the Liverpool Mercury, 12893 (6 May 1889, p. 8.)) It seems unlikely that the two businesses were running concurrently, but probable that Herbert needed to call on his father’s financial support to keep his first enterprise afloat, that Nathaniel had demanded a partnership, and then rapidly took sole control. This hints at a ruthlessness in Nathaniel’s nature, but also commercial acumen. By 1896 the firm was advertising its goods as

‘…grey cloth and coloured goods, printers, shirtings, dhooties, domestics, T cloths &c., dress zephyrs, galateas, flannelettes, handkerchiefs, stripes and checks, cotton, linen & silk mixed goods and label cloths.’

and had a branch in Glasgow.((It was listed as least until 1909 in Slater’s Directory for that year. Together with James Findlay and John Usherwood, two Glasgow-based muslin manufacturers, Nathaniel also had commercial interests in another Manchester business, the Victorial Frilling Manufacturing Company, based at Ancoats. See The Edinburgh Gazette, 27 October 1893, p. 1128-9.)) But following these business setbacks his son, Herbert, died in 1896 at the relatively early age of 36.((Herbert was a member of the 17th Lancashire Volunteer Corps (Rifle), and was appointed Lieutenant in May 1883 (London Gazette, 8 May 1883, p. 2427); he resigned the commission a year later (London Gazette, 27 May 1884, p. 2340).))

Nathaniel and Melicant’s third child was their only daughter, Melicent Estcourt (1864–1948), who married Captain Albert Henry Rishworth (1858–1937) in 1895:((The wedding was a large affair, with a reception at Nathaniel’s large house, ‘Sunnyside’, as reported in an extended piece in the Manchester Times, Friday, October 4, 1895)) at the time he was a partner, with a brother, in a corn mill in his home town of Keighley, Yorkshire but that partnership was dissolved in 1898,((London Gazette, 11 November 1898, p. 6630.)) and by the 1901 census his occupation was that of a coal merchant in partnership, it seems, with his wife’s younger brother. Arthur Harold Bradley (1865–1935) remains a shadowy figure,((He married Edith Eleanor Clough in Greenhays, on 24 April 1890 (see Manchester Courier, 24 April 1890, p. 8).)) but he was apparently in business as a coal merchant by 1891 at the latest, initially under his own name((An Arthur Bradley, a coal merchant in Manchester, was recorded in the 1891 census (Class: RG12; Piece: 3220; Folio 37; Page 8; GSU roll: 6098330), and an Arthur H. Bradley is recorded in Slater’s 1895 Directory (Part 1, p. 73) as being a coal merchant and living in Upper Chorlton Road.)) and by 1903 (and probably earlier) in the firm of Bradley & Rishworth.((See Slater’s Directory of Manchester for 1903, part 1, p. 672.)) However the partnership did not last, and by 1911 Rishworth was back in Yorkshire living with his family in Hull and working again in flour milling industry, though now as an employee.((See the 1911 census (Class: RG14; Piece: 28736).))

Rishworth had been a member of the 3rd Volunteer Battalion, the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) for many years, gaining promotion to Captain in 1885;((London Gazette, 21 August 1885, p. 3948)) he subsequently served in WWI, was promoted to temporary Major in 1916, was awarded a CBE, and by 1920 was Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel and Commander of the Hull Special Constabulary.((London Gazette, passim.)) Thereafter his fortunes seem to have waned: when probate was granted (to his daughter Nathalie (1897–1959)) his effects were valued at a mere £30, but his widow appears to have retained some capital (perhaps from her father) and after her death on 12 January 1948 her effects were valued at £1234 4s 4d.((Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England: 1948. Her daughter lived on in the family home and left effects worth £11,442. 18s 10d.))

Nathaniel’s fifth child, Gerald Thaniel (1868–1915) followed him into the chemicals business and by 1901 was described as a ‘Brewers Chemical Manufacturer’ suggesting that he may have been working in one of his father’s brewery supply businesses, though his census classification as ‘employer’ implies a managerial role. Interestingly, at the date of the 1901 census, both he and the youngest son, Alfred Estcourt Bradley (1869–1941) were not living with their father, but lodging together with a widow, Amelia M. Johnes, at 119 Withington Road at Moss Side, Manchester.((1901 Census (Class: RG13; Piece: 3708; Folio: 139; Page: 23).)) However, by 1911 the two brothers were again living with their father, at 52 College Road: Nathaniel had retired from trade but was frequently attending the police courts as a JP. Gerald was apparently managing the family business, but when he died in 1915 his effects were valued at a modest £488 16s 5d.((Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England: 1915.))

Fig. 2: Sunnyside Villa, 52 College Road. The villa was demolished in 2009. [Click on the image for a link to the original source.]

Alfred had adopted his father’s other trade, as a ‘Manufacturer of Grey and Coloured Goods’ by 1891, and was working as a ‘Cloth Agent’ in 1901 and 1911,((See the relevant entries in the censuses for 1891, 1901 and 1911.)) presumably with N. Bradley & Son. The rest of Alfred’s life is more or less undocumented though he married his mistress, Margaret Vennard (1875–1947) in 1915,((England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes (London, England: General Register Office), accessed via Ancestry.co.uk (27 July 2010). The online Vennard family tree (http://www.vennardfamily.com/charts/fchart1.pdf, accessed 27 July 2010) indicates that they had one daughter, Dorothy May Bradley (1903–1977), who was born out of wedlock.)) and in the same year, together with Francis Bradley, Bennet Collier and Albert Rishworth, acted as one of his father’s executors.((London Gazette, 30 April 1915, p. 4202.)) As might be expected, Nathaniel had died a relatively wealthy man, leaving an estate of £53,002 18s 11d. ((England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations),1861-1941.The National Archives currency converter (hereafter NACC) suggests that the estate would today be worth £2,282,306.85.))

Family – Parents

Given the commitment to energetic self-improvement on both sides of the Bradley family, it is perhaps no surprise that Francis Bradley((The spelling ‘Frances’ occurs in many of the primary sources.)) proved to have a wide range of interests which he pursued with some vigour, but what is striking is that he eventually extricated himself almost completely from the network of family business interests and forged an independent, and successful career for himself in law.((Unless otherwise stated this biographical outline is based on the two obituaries that appeared in The Times, on 5 September 1933, p. 22, and 7 September 1933, p. 16.)) Francis was born on 6 April 1862 and studied at Manchester Grammar School and later at Owens College, Manchester((Founded in 1851, in 1880, together with colleges in Liverpool and Leeds it formed Victoria University, before achieving independence as Manchester University in 1902.)) where he prepared for his father’s profession, by reading chemistry (1880–2). He subsequently undertook important research in Nathaniel’s laboratory, but in 1885 changed career path entirely, entering the new School of Law at Owen’s College, becoming the Dauntesey Law Scholar((One of two scholarships (the other was in medicine) founded in the late 1870s from a bequest by Mrs Catherine Dauntesy Foxton; see the British Medical Journal 1/903 (20 April 1878), 581.)) the following year,((He passed the Intermediate Examination in Law in January of that year (The Leeds Mercury, 14908 (19 January 19 1886), p. 3).)) and Associate in 1888. While at Manchester Francis took three degrees: M.A. (London), M. Com and LL.B (a first, in 1888) and subsequently took a LL.D. at London in 1895.((The Leeds Mercury, 17741 (14 February 1895), p. 5.)) By this time Francis was also moving in Manchester Literary circles, and having been elected a member of the Manchester Literary Club in 1884, published two Sonnets in the vol. XII (1886) of the Club’s periodical, The Manchester Quarterly.

Fig. 3. Two Sonnets by Francis Ernest Bradley (Manchester Quarterly, vol. XII (1886)) [For a larger version, click on the image.]

In 1886 Francis Bradley entered Grays Inn,((See The Register of Admissions to Gray’s Inn 1521–1889, ed. Joseph Foster (London, 1889), p. 495.)) won a two-year scholarship in jurisprudence and Roman law worth £100,((Awarded by the Council of Legal Education in June 1886 (The Standard (London), 19329 (25 June 1886), p. 3; and 19335 (2 July 1886), p. 5).)) followed by the Bairstow Scholarship in 1888((See The Blackburn Standard: Darwen Observer, and North-East Lancashire Advertiser, 2732 (23 June 1888), p. 8.)) and was appointed the Arden Scholar in 1889, the year he was called to the bar, joining the Northern Circuit. In 1921 Francis Bradley was appointed Judge of Country Courts No. 4. While practicing as a barrister in the 1890s he also lectured and tutored in law at Owen’s College, and by 1901 was affluent enough to have a household at 192 Upper Chorlton Road((For a photograph (c. 1960), see http://www.images.manchester.gov.uk/web/pages/common/imagedisplay.php?irn=16485&reftable=ecatalogue&refirn=71825 (accessed 22 July 2010).)) that included four servants.((1901 Census (Class: RG13; Piece: 3666; Folio: 49; Page: 39.)) Little is known of his investments, but he was a director of Clarkson’s Old Brewery, Barnsley Limited which in the early 1890s was paying annual dividends of 6-8%((The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent 11844 (3 August 1892), p. 5.)) and by 1899 he was chairman of the board of directors.((The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, 13970 (21 August 1899), p. 3.)) In later years Bradley played a continuing role in education, as the author of a number of legal text books,((F. E. Bradley’s Company Handbooks, 2 vol. (London: Stevens & Haynes, 1917); Company Principles and Precedents (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 1920); [with Frederick Hungerford Bowman:] The Inventor’s Handbook of Patent Law and Practice (London: Ewart, Seymour & Co., 1914). (Bowman was a Manchester colleague who was one of the Bradley’s proposers for membership of the Royal Society of Scotland).)) as examiner in equity to the Council of Legal Education (1914–17) and as a member of the Court of Manchester University (1921–30). Bradley remained interested in scientific and economic research, and was elected a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in March 1916;((See the biographical entry in the list of former Fellows of the RSE (a valuable source of supplementary information generally): http://www.rse.org.uk/fellowship/fells_indexp1.pdf (accessed 22 July 2010).)) in January 1905 he was admitted to the Glaziers Company (of which he was Master in 1923–4) and on 27 January was made a freeman of the City of London.((Freedom admissions papers, 1681–1925: London Metropolitan Archives. COL/CHD/FR/02, CFI/2479/26.)) One further aspect of Francis Bradley’s life was his membership of the freemasons. This was a family tradition, and his father and all his brothers were masons: he was initiated to the Talbot Lodge, Old Trafford on 16 July 1897, and transferred to the Northern Bar Lodge on 12 June 1898.((See Library and Museum of Freemasonry (London): Freemasonry Membership Registers, Country W 2074-2257 to Country X 2258-2380, Reel Number: 19, opening 258 and Membership Registers: London E 1269-1540 to London F 1541-1679, Reel Number: 34, opening 110.))

When and where Francis Bradley met Bessie Smith, his future wife, is unknown, but the fact that one of her brothers, Arthur (1864–1940), was a solicitor in Wigan suggests that Francis may have come to know the family initially through professional contact. Some of Lionel’s mother’s family had, like the Bradley’s, moved out of poverty into modest prosperity. Bessie Smith’s paternal grandfather, Joseph Smithies (b. c.1806) was, like Robert Bradley, a weaver, but by 1858 her father, John Smith (1834–1896) was already described as a ‘Clerk and agent’((Baptismal record of his daughter, Sarah Hindley Smith (1858–64), 7 July 1858, St Oswald, Winwick, Lancashire.)) and in 1861 was a Colliery Agent, before establishing himself as a Coal and Slate Merchant c.1872. He was also involved in local politics and by the time of Bessie’s marriage was an Alderman as well as a J.P. in Wigan, and had served as the Mayor of Wigan in 1889–90.((See the Local Chronology pages on http://www.wiganworld.co.uk/stuff/ (consulted 26 September 2010).)) At his death he left a substantial estate of £62,695 10s 6d.((England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations),1861-1941 (NACC: £3,577,406.66).)) Similarly, her mother’s father, Thomas Pennington, was employed as a bricklayer in 1836,((Baptismal record of his son, St Oswald, Winwick, Lancashire, England.)) but by 1841, was a ‘Farmer of 19 acres, employing 2 labourers’.((1841 Census (Class: HO107; Piece 524; Book: 16; Civil Parish: Winwick; County: Lancashire; Enumeration District: 5; Folio: 6; Page: 7; Line: 22; GSU roll: 306910). His son Joseph (Bessie’s uncle), combined both his father’s occupations and in 1881 was a ‘Farmer Of 200 Acres Employing 7 Men & 1 Boy Also Builder Emp 30 Men Earlestown’.))

Very little is known about Bessie herself. She was born at Ince in Makerfield on 13 November 1870 and was baptised at St Oswald, Winwick, on 25 January 1871. She and Francis were married on 12 August 1891 at All Saints, Wigan((See http://www.lan-opc.org.uk (accessed 22 July 2010) and Manchester Times, 21 August 1891, p. 8.)) and by the end of the century had three children, of whom Lionel Bradley was the last. Their first, Reginald Ernest, was born on 6 September 1892,((For the baptismal record, see: http://www.lan-opc.org.uk/Prestwich/stmary/baptisms_1891-1893.html (accessed 18 July 2010).)) and was sent away to school at Lawrence House, St Anne’s-on-Sea and then Haileybury in Hertfordshire (1906–9).((See http://haileybury.com/honour/HAILEYBURY%201916.htm (accessed 18 July 2010).)) He went up to Manchester University in 1909, reading arts and joining the OTC before graduating in 1911. Reginald was subsequently articled to the Chartered Accountants Neild Isaac Son & Lees,((See Manchester University: Roll of Service (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1922) pp. 9–10.)) but enlisted on 7 October 1914 and began his war service as a Corporal Motor Cycle Dispatch Rider in the Royal Engineers. In 1915 he married Frances Marjorie Gibbons, the daughter of a Stretford pharmacist, Walter Gibbons: although the marriage was in London it seems very likely they had known one another when growing up about 1½ miles apart in the suburbs of Manchester.((Frances subsequently, in 1920, married Vernon Howard Seddon (1889–1962), had two children, and died in 1954. I am most grateful to Doug Summers – a distant relation of the Bradleys – for his help in documenting Reginald Bradley’s marriage.)) Reginald was gazetted in 1916 and subsequently promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in the RE, but died of wounds in France on 23 December 1916.((All that survives of his war record are the cards relating to his war medals (NA, Catalogue Reference:WO/372/3, Image Reference:12884). This indicates that he joined up in 1914 and was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. See also website recording the war dead of Sale, accessed 1 June 2010 (n.b. this gives the date of death erroneously): http://www.traffordwardead.co.uk/index.php?sold_id=s%3A8%3A%22711%2Csale%22%3B&letter=&place=&war=I&soldier=Bradley)) The Bradley’s daughter, Mary Melicent, was born at the family home on 10 March 1895 and died at the Royal Infirmary, Manchester on 30 July 1925, of head injuries sustained when her motor scooter collided with a tram;((Information from copies of the birth and death certificates; the later describes her as a ‘spinster of no occupation’.)) sadly that is all that is known of her short life.

Biography

Fortunately Lionel’s education and professional life can be traced in some detail in a number of sources, chief among them two obituaries, which appeared in the Library Association Record((The obituary was signed Robert Hutton (see below): The Library Association Record, February 1954, 71.)) and The Times,((The Times, 4 January 1954, p. 8. A brief announcement had appeared in the 1 January issue, p. 8, and a short appreciation by Geoffrey Handley-Taylor appeared there on 7 January (p.8). Obituaries also appeared in the Manchester Guardian and the Daily Telegraph on 2 January 1954. (My thanks to Peter Halsey of the London Library for drawing these last two to my attention.) )) and the brief notes made by the Provost of Queen’s College, Oxford, when Bradley went up in 1917.((Kindly transcribed and sent to me by Michael Riordan, Archivist of St John’s and the Queen’s Colleges, Oxford (9 March 2010).)) He had been educated at Manchester Grammar School between 1909 and 1917((According to Jeremy Ward, the archivist of Manchester Grammar School, who has kindly supplied the details of Bradley’s career at the School (e-mail, dated 13 September 2010), Lionel had probably been educated at home before entering the school.)) where up to 1913 he had an impressive academic career on the Classical Side, studying Latin and Greek: he was top of his class in his first and last years and was never placed lower than sixth. Bradley then moved to the Classical Sixth where, initially in competition with pupils up to three years older, he moved from 12th (out of 26) at the end of his first year, to third. He was awarded the Shakespeare Scholarship (given to boys who were outstanding in English) and at Christmas 1916 gained a scholarship to Queen’s College. He stayed on until the summer of 1917, finishing 3rd in a cohort of 24, and went up to Oxford in October 1917, to read Classics.

Lionel’s subsequent academic career, unlike his father’s, was not especially distinguished: he took a 2nd in Classical Moderations in 1919 and a 3rd in Literae Humaniores in 1922. He had apparently been absent from the College in 1920–1, perhaps related to ill-health: the Provost had noted that he was delicate, describing him as rheumatic, but adding that he could play cricket & tennis a little and was in the school OTC for the shorter parades.((However that was also the academic year immediately following his sister’s tragic accident.)) It was presumably for this reason that Bradley had not been called up for war service, but relegated to the reserve, subject to examination every 6 months. Further unspecified bouts of ill-health are referred to in the Bulletins,((For example, between 19 March–14 April 1942 he was at a nursing home: see the entry covering these dates in Broadcasts heard from 7 September 1941 to 19 Sept. 1942 (GB-Lrcm).)) and Bradley was to die relatively young.

The archives of Manchester Grammar School do not record Bradley participating in any extra-curricular activities while a pupil, though the Queen’s Provost noted that Bradley took photographs, and was fond of music, but was not a performer: an intriguing comment that frustrating leaves the nature and extent of Bradley’s musical knowledge unclear. In the Bulletins Bradley occasionally refers to having a score to hand, but usually for vocal works, suggesting that he may have been mainly concerned to be able to follow the sung text. So far there is very little evidence of interest in music or the other arts amongst the Bradley or Smith families: indeed the sole reference to music predates Lionel’s birth, and appears in the newspaper report on his aunt Melicant’s wedding reception on 25 September 1895, which included a violin and organ recital during the signing of the register, and a concert provided by a ‘carefully selected contingent from Sir Charles Hallé’s orchestra’.((Manchester Times, 7 October 1985, Supplement, p. 5.))

Despite the fact that during the interview with the Provost he had declared that he was not interested in any of the professions, Bradley was called to the Bar in Gray’s Inn in 1924 and joined the Northern Circuit. In this he was following in his father’s footsteps, but just as his father had done, he quickly changed career path. He probably never practiced law, and later in 1924 he was appointed to the Library of the University of Liverpool, gaining promotion in 1931 to become the first holder of the post of deputy librarian. From then until 1936 he was active in the Library Association, contributing to conferences and to the Year’s Work in Librarianship.

On 8 July 1931 Bessie Bradley died at home, at the age of sixty.((See the obituary of F.E. Bradley, The Times, 7 September 1933, p. 16. and Law Society Journal, 72 (1931), 50. Probate was granted to her brother, Arthur Smith, on 14 September 1931, and her effects amounted to £4549 8s 10d (NACC: £152,042.34).)) Whether or not this event was unexpected, Lionel probably failed to anticipate that two years later, on 15 July 1933, his father, by then 71, would marry for a second time. His bride was Elsie Reynolds, a spinster; the place was the Fylde district registry office, and his son seems not to have been present. The bride’s father was George Reynolds but otherwise little else is known about her beyond the fact that at the time of the marriage she was she was living at 14 Norfolk Road, Lytham, less than four miles from Francis Bradley’s house in St Anne’s on the Sea.((Copy of the marriage certificate.)) Unfortunately the elderly husband had little opportunity to enjoy connubial bliss: while on holiday at the Grand Hotel Eastbourne later that summer he was taken ill, and on 3 September died at the hotel from a cerebral haemorrhage, with Lionel at his bedside.((Copy of the death certificate; at the time Lionel’s address was 9 Bold Place, Liverpool.)) His estate was relatively modest – £14,923 3s– perhaps diminished by the effects of the 1929 crash, and was left to his widow.((England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations),1861-1941; NACC suggests that the estate would today have a spending power of £551,858.09.))

In 1936 Lionel Bradley left his university post,((According to John Wells (Rude Words: A Discursive History of the London Library (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 203) he was sacked because of an indiscretion with a male undergraduate.)) and moved to London, taking up residence in a flat at at 32 Cranley Gardens, Kensington where he remained for the rest of his life. The next four years he seems to have spent his time attending and writing about ballet, and going to other performance events (including a short trip the Paris in June 1938).((The bulletins devoted to opera and concerts include reports on four such events he attended in Paris between 5–11 June 1938.)) However, the move to London not only provided Bradley with greater access to ballet performances, but to the ballet world as whole. He came to number dancers, choreographers and balletomaines as close friends, and quietly played a notable supporting role, not least in the plans to form a London Archive of the Dance in emulation of similar repositories in Paris and New York. This had its origins in the activity of the Ballet Guild:((Kathrine Sorley Walker, ‘Cyril W. Beaumont: Bookseller, Publisher, and Writer on Dance Part Two’, Dance Chronicle, 25/2 (2002), 275. The author of the article ‘was co-opted on a voluntary basis as honorary archivist.’))

It was an organisation that ran a small performance company, ballet classes, and club events, and it was proposed that it should also build up a library and archive. This was largely the idea of Cyril [Beaumont], Lionel Bradley (a librarian, ballet writer, collector, and researcher), and Deryck Lynham, a younger man….The archive began modestly but was built up by donations and handed over in 1945 to a trust company as the London Archives of the Dance.

The formation of the archive was announced in a letter to The Musical Times in May 1945:

[T]he London Archives of the Dance has been constituted by a Trust Deed, and the Trustees hope, as soon as funds and the post-war situation permit, to open premises in Central London, where its collections may be housed and displayed and made available to anyone interested in dancing and the allied arts….

As the nucleus of its collection the L.A.D. has been given the 3,000-odd books, programmes, pictures etc. assembled by the Ballet Guild in the past four years. It has also bought, by means of a loan, an interesting collection of musical scores of the old Alhambra ballet, and is negotiating for the purchase of a valuable collection of some 250 musical scores of Ballets ranging from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries.

The trustees were Beaumont (Chairman), Bradley (Hon. Treasurer), Lynham (Hon. Secretary) and Christmas Humphreys.((Humphreys 1901–1983 was a controversial barrister and later a judge at the Old Bailey. After the death of Lynham in 1951 and Bradley in 1953, Beaumont effectively made all the decisions (see Kathrine Sorley Walker, ‘Cyril W. Beaumont: Bookseller, Publisher, and Writer on Dance, Part Three’, Dance Chronicle 25/3 (2002), p. 461).)) In fact the plans outlined were never fulfilled: in 1957 Beaumont had been promised a small flat where the Archive could be housed and made available, but these plans fell through((Ibid., 449, 451.)) and the Archive was eventually transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1968.((Ibid., 461–2.)) By this time the collection had grown significantly thanks to various additions. Early in 1954 P.W. (Bill) Manchester, a friend of Bradley and fellow ballet-lover, had written to the Archives:

I do hope Lionel made arrangements about leaving all his diaries and cuttings to the Archives – they will be an invaluable and super-accurate record of practically everything that has happened to the ballet in England for as long as there has been any English Ballet. His records must be an Archives of their own.((Letter dated 1 February 1954: V&A Theatre Collection, London Archives of the Dance – Bradley Correspondence, Bradley Box 1 (THM/238/5).))

Thanks to Rex Hillson a substantial part of Bradley’s ballet-related collection (including the Ballet Bulletins and books) did indeed pass to the Archive.((There are three letters from Hillson in the Archive that deal with aspects of the distribution of the collection: Bradley Box 1 (THM/238/5).))

Having established himself in London, Bradley returned to his chosen profession and accepted the post of assistant secretary and sub-librarian at the London Library, where he was responsible, amongst other things, for a revision of the subject index.((According to John Wells, op. cit., p. 176, ‘soon after he joined the library he was given permission to keep his ballet notes in a room in the basement’.)) This post hardly curtailed his attendance at musical events, as the series of Bulletins attest, and the Library Association obituary opined that Bradley ‘could have achieved eminence in librarianship, but music and ballet were his real interests’ and added that

His friends will remember him as a “wary and acute reasoner” – witty, urbane, the most generous of eccentrics and the most open-handed and forgiving of friends.

One of his colleagues from his years at the London Library, Miss Joan Bailey, has the warmest of memories of him, as a kind and supportive librarian. Indeed, on one occasion he stepped in to protect her from a male member of staff, an old porter who had ‘made a grab’ for her and whom she had rebuffed. Shortly afterwards, while helping a library member, she had borrowed some string from the porters’ lodge to tie up a parcel of books:

Auckland…came back and saw what I had done. He absolutely pitched into me: I had stolen string, and there was a war on, and I was doing his work. Of course I realised later on…he was getting back at me. But he didn’t know, and I didn’t know, was that there was a partition between the lodge where the porters were and the main return desk. Behind that partition was Mr Bradley, and I was standing there – well I just didn’t know what to say , it was beyond words. Bradley came through and he said to Auckland:

‘If ever I hear you speaking to Miss Bailey like that again you are OUT and permanently OUT.… Don’t bother her any more.’…

I just said ‘thank you’ and went back to my work.((Interview with Joan Bailey, recorded at the London Library, July 2010.))

On the other hand he was one of the senior librarians, and some of the younger members of staff were clearly intimidated by him:

I said how much I liked Lionel Bradley, [and Barbara] said

‘Oh God, I was terrified of him.’

I said, ‘What! He was lovely,’ and she said,

‘Well, working in the cataloguing room, every single morning he would come up and he would sit either on the radiator, if they weren’t too hot, or sit on the window sill, and read his copy of The Times and nobody dared speak or say anything while he was reading.’

I laughed and said ‘That sounds like Lionel…..’((Ibid.))

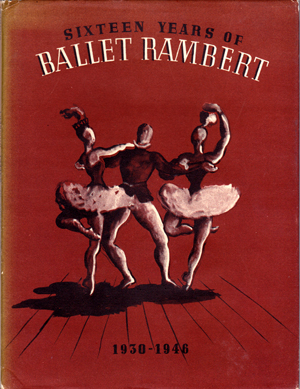

Bradley published only one book himself:((His surviving papers in the V&A Theatre Museum provide clear evidence, however, that he was planning a history of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet.)) Sixteen Years of Ballet Rambert, decorations by Hugh Stevenson (London: Hutchinson, 1946),((The dedication reads: Dedicated to the memory of |DAVID MARTIN | poet, artist and dancer, 1919–1943 | Tu quoque magnum | Partem opera in tanto, sineret dolor, Icare, haberes. [You too, Icarus, should have borne a great part in that great work.]

David Martin Penny, was born in Lambeth, 13 December 1919 (he may have been illegitimate, as his mother’s maiden name is also given as Penny). He was a W/Sergeant [i.e. War Sargeant] in the Glider Pilot Regiment, and was killed in a flying accident on 15 November 1943. See also Michelle Potter: Dame Maggie Scott: A Life in Dance , 61–2 (with a photograph): Scott and Martin were lovers; the volume is also of interest because it quotes extensively from Bradley’s ballet bulletins.)) but he also contributed to, amongst others, the magazine Ballet (1939; 1946–52), whose founding editor, Richard Buckle, appended a telling personal memoir to The Times obituary:

….Everything he saw or heard he wrote down: and everything anybody else wrote down about ballet he found mistakes in and wrote to them about. He brought fault-finding to a fine art, and was always so kind and amused about it. I think of him, stout, bearded, quiet, shy, but twinkling behind his spectacles, going every day from his flat in South Kensington to his work at the London Library. I think of him hastening slowly home or to Covent Garden at the end of a busy day. But his day really only began after dark; and my most characteristic picture of him would show him seated in the untidy study after an excellent dinner cooked by the devoted Mrs. Whitman with a glass of brandy beside him, surrounded by piles of books, listening to Mozart. When one left him he would be looking things up and writing letters until three in the morning. He had many friends among dancers – they used to call him “Uncle Leo” – but I think he was rather lonely. I last saw him just before Christmas and he said he thought Dutilleux wrote very good ballet music. He died quietly after a day’s work….

This comment about his friendships can be placed in context by a reminiscence of Joan Bailey:

There was the lady in charge of the desk [at the London Library]… and she talked to me quite a lot, and just in passing I said to her:

‘Why are there always these very pretty blond young men waiting every night outside the Library … for Mr Bradley?’

And she turned … looked at me [and] said ‘It’s time you grew up.’

I said ‘What do you mean?’

She said ‘He’s queer.’

Well, she was so dismissive of me, I couldn’t ask what that meant!((Interview, July 2010. Miss Bailey recalled that ‘In one way the library was considered a hothouse for these gays, there were so many of them.’ Another of Bradley’s colleagues, Audrey Tate recalls, that he sometimes entertained his friends in Library staff room after work (reported in a letter from Joan Bailey to the author, 30 August 2010), and that one of the regular visitors was a distinguished dancer from the Ballet Rambert, Leo Kersey (letter from Joan Bailey to the author, 6 September 2010).))

But whatever the other attractions, the companionship was clearly important for Bradley, and on at least one occasion he reports deciding not go to a concert, listening to the broadcast instead, because he didn’t want to attend on his own. Although Miss Bailey was doubtful about Buckle’s comment about the possibility of his loneliness, the Bulletins offer some support to his speculation.

On 30 December 1953 Bradley wrote up a report on a broadcast concert by the Harvey Phillips String Orchestra, in what proved to be the last of his Bulletins. He failed to turn up for work the following day and was found dead in his flat, having suffered a cerebral haemorrhage brought on by hypertension.((Death certificate. There was an autopsy, but no inquest. According to Joan Bailey (interview, July 2010), the police, who had been alerted by the Librarian of the London Library, had to break in.))

Will and Estate

In financial terms Lionel Bradley left a modest estate. His flat at 32 Cranley Gardens, Kensington, was rented, but his property, cash and investments were valued at £11368 9s 2d (gross) for probate. He had signed his last will on 8 July 1950, adding two codicils on 8 and 13 October 1952:((Probate was granted at the Liverpool District Probate Registry on 15 March 1954 (I am most grateful for Bruce Ramell for researching this, and obtaining a copy of the will). The NACC value for the estate is £198,038.54.)) the provisions offer indications – though little more – of both old and changing relationships.

Of the former it is interesting to note that the first codicil requires that Messrs Arthur Smith & Broadie-Griffith of Wigan ‘be employed as solicitors in connection with [the] estate’: this was the firm established by his uncle (on his mother’s side) in 1887.((It is still in existence: see http://www.arthursmiths.co.uk/about.php (accessed 5 November 2010).)) On the other hand, the disposal of his ‘personal chattels’ was revised: these (together with a bequest of £100) were originally to pass to Robert Hutton (then Librarian of King’s College, London) or if he predeceased Bradley, William Reginald (=Rex) Hillson of Liverpool, or if he did not survive Bradley either, to Kenneth Douglas White (at that time, Professor of Classics at Rhodes University College in Grahamstown, South Africa). One of the main effects of the first codicil was to reverse the order of the first two potential beneficiaries, though what provoked this change of mind is unknown.((Bradley was not quite up-to-date: the codicil fails to reflect the transformation of White’s employer into Rhodes University in 1951 (see http://www.ru.ac.za/rhodes/introducingrhodes/historyofrhodes (accessed 5 November 2010).))

Both Hillson and White were graduates of Liverpool University and it is striking that four of the financial bequests were linked to other alumni of the University: Walter Pullen, who received £50, Philip Ainsworth Gaskill, whose daughter Gillian (Bradley’s god-daughter) received £250, and Robert Alfred Armstrong Dodds,((In 1948 Dodds became the last person to join the group of recipients of the Concert Reports, and in the late 1940s his address was Eastfield Road Junior School, Enfield Wash, Middlesex. He was born in Norton, Durham, in 1906 and after Enfield he moved in the summer of 1951 to 13 Junction Road, Norton, Stockton-on-Tees and then again in early 1953 to 262 Norton Road; he was still living in the town when he died on 31 December 1961 at Poole Hospital, Nunthorpe. His widow was Marguerite Alma Dodds (née Hediger): they were married at Stockton in 1936.)) whose son (Bradley’s god-son), received £50, but on attaining his 25th birthday would receive half of the residual financial estate. The interest on the other half of this estate((Or the whole of the estate if Timothy Dodds died before attaining his 25th birthday.)) was to be paid to Arthur Richard Owen, who was at that time at Doncaster Training College, and after his death was to be paid to his wife, Erna.((Arthur R Owen married Erna Brucker in Liverpool in the summer of 1935 (General Register Office: England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes).)) Following their deaths the capital was to be divided equally between Manchester Grammar School, Queen’s College, Oxford, and the University of Liverpool with a request for preference to be given ‘to any proposal that the said bequest shall be devoted to the library of the body concerned, or, alternatively, to the assistance of students engaged in the study of, Greek, English Literature, German or Music’. Bradley asked that books purchased or bursaries established through this provision should, in the case of MGS be associated with the name of J. R. Broadhurst (‘one-time Master of the Classical Transitus’((Interestingly Broadhurst was also closely associated with music provision at MGS and became the school librarian (see Alfred A. Mumford, The Manchester Grammar School 1515-1915: A Regional Study of the Advancement Of Learning in Manchester since the Reformation (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1919), 371, 394.))), in that of Queen’s, with Edward Mewburn Walker (‘one-time Provost’, 1857–1941), and that of Liverpool University, John Sampson (‘one-time Librarian’, 1862–1931((Librarian of Liverpool University, 1892–1928. See http://sca.lib.liv.ac.uk/collections/colldescs/gypsy/Sampson.htm (accessed 6 November 2010).))).

The first codicil in 1952 made a number of modifications, including three to financial bequests. Bradley’s housekeeper, Mrs P. J. Whitman, was to receive £100 instead of £50, while the bequest of £50 to Michel [sic] Hogan of Leicester, was revoked entirely, as was the bequest to A. R. Owen although in this case it was granted instead to Walter Gore of Linden Gardens, London for the duration of his life alone, after which the provisions listed above were to be followed. At present the circumstances behind these modifications remain unknown, but the last of these certainly reflects Bradley’s profound love of ballet, since Gore (1910–79) was a distinguished dancer, choreographer and manager.((See Clement Crisp, ‘The Life and Work of Walter Gore: A Tribute in Four Parts – Introduction’, Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 6/1 (Spring, 1988), 3-6 and http://www.australiadancing.org/subjects/33.html (accessed 6 November 2010). On at least one occasion – 28 March 1949 – Gore and Bradley attended a concert together, a concert given by Britten, Pears and the Boyd Neel Orchestra at Chelsea Town Hall.))

The remaining bequests were all to charities and reflected Bradley’s interests in the performing arts: £200 to the Sadlers Wells Ballet Benevolent Fund, £100 to the Hallé Concerts Society, £100 to the Hallé Orchestra Pension Fund and £50 to the Dolmetsch Foundation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank a number of individuals for their generous help and scholarly support:

David Allen (Royal Society of Chemistry)

Joan Bailey (London Library)

Paul Collen (RCM)

Oliver Davies (RCM)

Robert Gill (Barn Theatre)

Dr Katy Hamilton (RCM)

Martin Kay (University of Liverpool Library)

Michael Kennedy

Inez Lynn (London Library)

Rachel Neale (Manchester Grammar School)

Jane Pritchard (V&A Museum, Theatre Collection)

Brice Ramell

Michael Riordan (Archivist, St John’s and the Queen’s Colleges, Oxford)

Stuart Robinson (Hallé Orchestra)

Doug Summers

Jonathan Summers (British Library)

Ruth Walters (Westminster Music Library)

Jeremy Ward (Manchester Grammar School)

Peter Wing

The quotations from the Concert Bulletins are reproduced by kind permission of Christine Angel.

This website by Paul Banks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]()

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

Printing and footnotes

If you wish to print this essay, the print function in your browser should provide a satisfactory version except that, because of the plugin I am using to generate the online footnotes, these will be printed not at the end but in the text within double parentheses.