Lionel Bradley: One Man’s Britten

Over the last twenty years or so, thanks to a number of projects based to a greater or lesser extent in Aldeburgh, we have gained a much more extensive knowledge about when and where Benjamin Britten’s music was performed, and the responses of professional reviewers are fairly well known. But what about the context in which Britten’s early public career was played out, what did music lovers hear, where, and how did they listen to this music and what did they make of it? A discovery in the Portraits and Performance History Collection of the Centre for Performance History (CPH) at the Royal College of Music shed some light on some of those questions.((The Centre for Performance History was closed in 2014 and its collections distributed between the RCM Museum and the RCM Library.))

In 2008 the RCM collection that since 1971 had been established and built up as the Department of Portraits and Performance History (DPPH), was moved from the 1894 Blomfield Building in Prince Consort Road to a newly adapted, air-conditioned facility at the College’s hall of residence, College Hall, in Hammersmith. This major task involved packing extensive components of the collection that had remained untouched, unlisted and, in some cases, unknown, for some time. However, this process had to be accomplished very rapidly, so there was no time for examination. Fortunately the unpacking process was more leisurely, and towards the end a box file emerged which had attracted no-one’s attention.

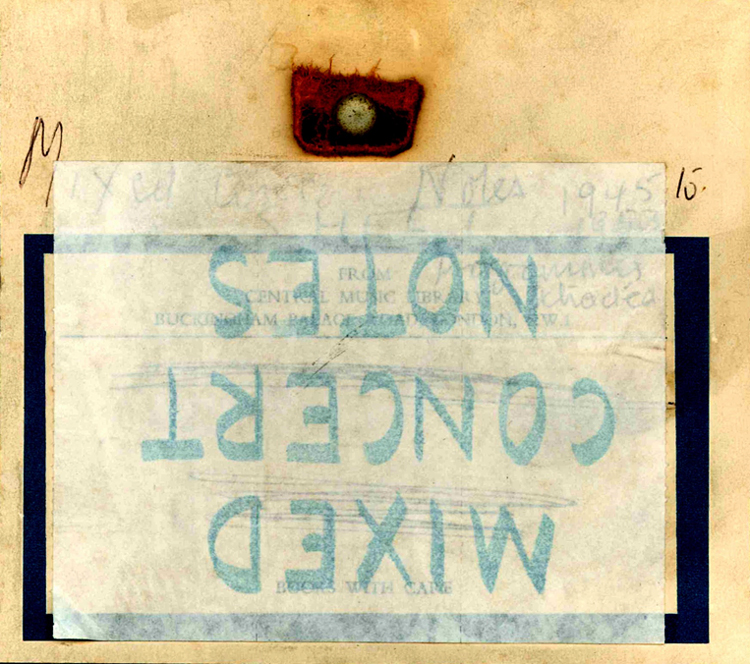

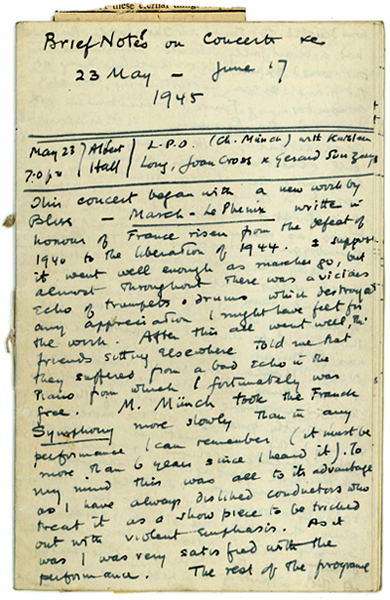

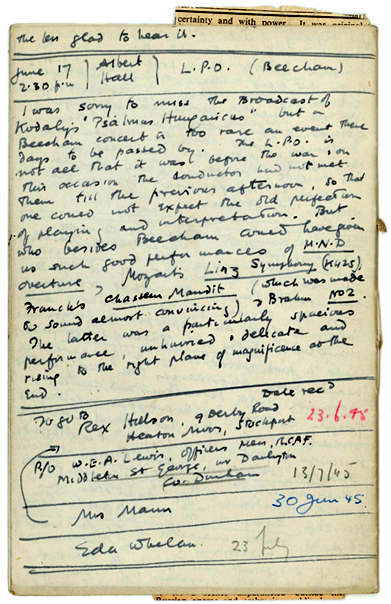

It was labelled MIXED CONCERT NOTES: interesting enough to encourage me to open it and explore. What it contained, alongside notebooks and other documents, was a large number of bundles of hand-written notes, home-made fascicles consisting of single sheets of paper stitched together by hand. By chance the first one I examined was headed Notes on Concerts etc. 23 May – June 17 1945. My first thought was to wonder whether there was an entry for the Wigmore Hall introduction to Peter Grimes or even a report on one of the early performances of the opera. In fact, to my surprise and delight, the writer had attended the introduction and the opening night: by now I was seriously interested in this collection.

The first major problem in assessing its significance was the fact that there was nothing obvious that identified the writer: a crucial piece of contextual evidence. If they were the work of a professional critic they would probably relate to a fairly familiar body of surviving literature; if not they might shed light on the responses of ordinary members of the concert-going public, a much rarer documentary survival. In the event it emerged that they had been written by a highly informed individual on the boundary between these two communities, who had worked on the fringes of ballet criticism, but for whom music remained a hobby. Nevertheless this was pursued with passion, a very systematic approach to documenting listening experiences, a wide knowledge of repertoire from the 18th to the mid-20th century (clearly reinforced by radio listening and a substantial collection of records), and a critical intelligence.

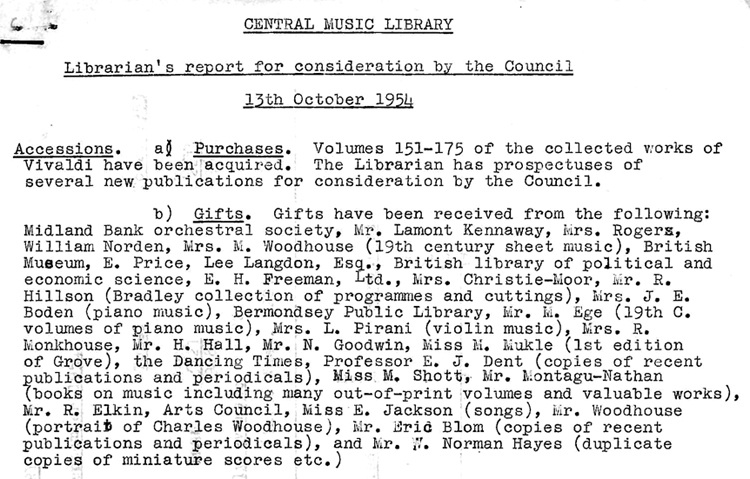

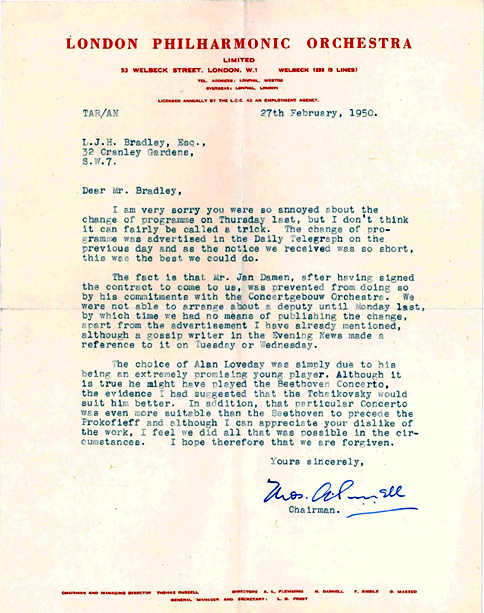

The first clue to the provenance of the collection was the box in which it was contained, as this had a Central Music Library label beneath the current one. Fortunately a 1981 report to the Council of the RCM by Oliver Davies (Keeper of the Department of Portraits and Performance History) recorded the transfer of a large collection of concert programmes from the Central Music Library: when space there had needed to be cleared a substantial number of files (also including press cuttings and programme notes from the Edwin Evans Collection) were transferred to the DPPH. It seemed possible that the material moved in 1981 was rather more disparate than Oliver Davies’ report had suggested, and that the manuscript concert notes formed part of the consignment. A clue to the identity of the author of the reports emerged as the collection was sorted by Dr Katy Hamilton, at that time the Junior Fellow in the CPH, and it came from two letters from early 1950 inserted into one of the Bulletins: they are replies from Thomas Russell, the Chairman of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, to letters complaining about the late substitution of Alan Loveday as soloist and the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in a recent LPO concert; the addressee was L.J.H. Bradley of Kensington.

Fig. 2: Letter from Thomas Russell to Lionel Bradley, 27 February 1950. (Royal College of Music Library)

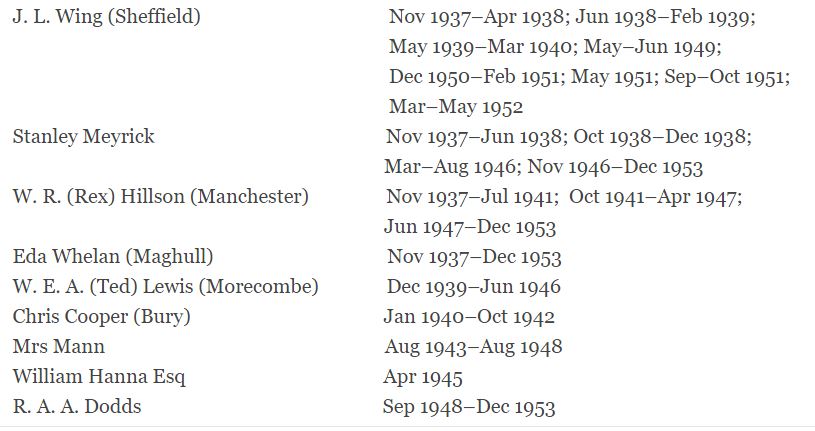

Further research suggested that this was Lionel Bradley, a music-lover with close ties to the North West of England, and with Manchester and Liverpool in particular. Armed with all this information, and the date of Bradley’s death (December 1953) Ruth Walters at the Westminster Music Library (successor to the Central Music Library) was able to locate the internal report noting the deposit by Rex Hillson of the ‘Bradley collection of programmes and cuttings’ in 1954. Hillson was for many years one of the recipients of the Bradley’s Bulletins, and inherited his friend’s personal chattels in 1954.

So, who was Lionel James Herbert Bradley? The main sources of biographical information traced so far are two obituaries, which appeared in the Library Association Record((The obituary was signed R. Hutton: The Library Association Record, February 1954, 71.)) and The Times,((The Times, 52820 (4 January 1954), p. 8; a further tribute by Geoffrey Handley-Taylor was printed on p. 8 of the 7 January edition.)) and the brief notes made by the Proctor of Queen’s College, Oxford, when Bradley went up in 1917.((Kindly transcribed and sent to me by Michael Riordan, Archivist of St John’s and the Queen’s Colleges, Oxford (9 March 2010).))

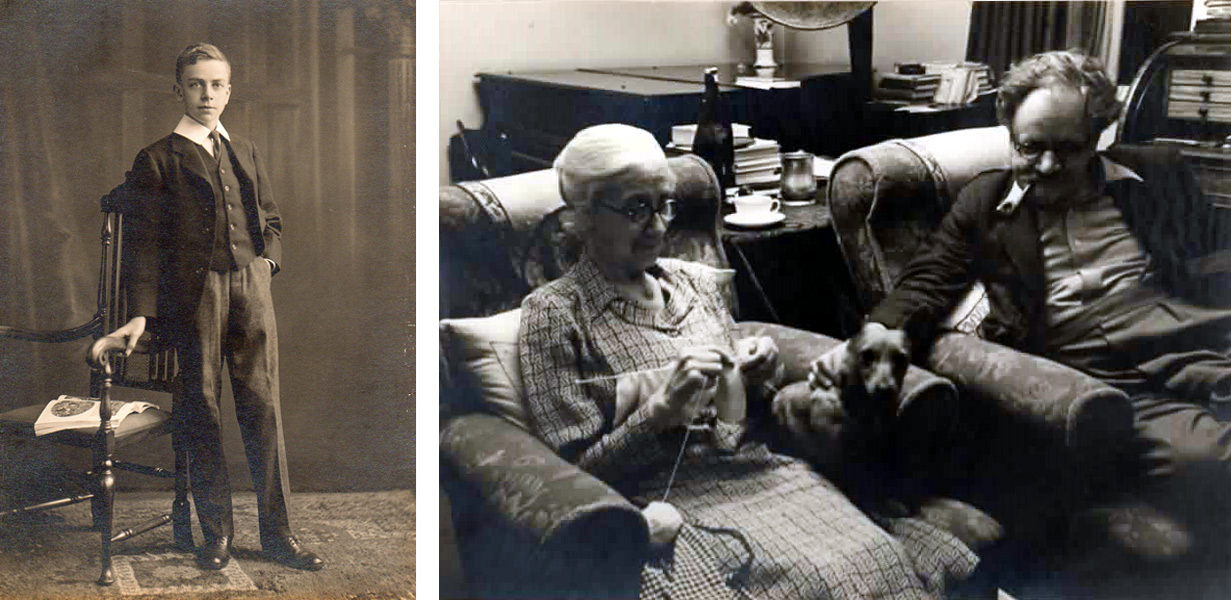

Lionel James Herbert Bradley was born on 21 January 1898 at Stratford, Lancashire, the son of a barrister (later a judge), F.E. Bradley Esq., of Chorlton-cum-Hardy.((For more detailed biographical information, see Lionel Bradley: A Family History and Biography.)) He was educated at Manchester Grammar School for six years and entered Queen’s College, Oxford in October 1917 as a Scholar reading Classics. His academic career there was not hugely distinguished: he took a 2nd in Classical Moderations in 1919 and a 3rd in Literae Humaniores in 1922. He had apparently been absent from the College in 1920–1, perhaps related to ill-health. The Proctor had noted that he was delicate, describing him as rheumatic, but adding that he could play cricket & tennis a little and was in School OTC for the shorter parades. It was presumably for this reason he had not been called up for war service, but relegated to the reserve, subject to examination every 6 months. Further unspecified bouts of ill-health are referred to in the Bulletins, and Bradley was to die relatively young.

The Queen’s Proctor also noted that Bradley took photographs, and was fond of music, but was not a performer, an intriguing comment that frustratingly leaves the nature and extent of Bradley’s musical knowledge unclear. Despite the fact that during this interview he had declared that he was not interested in any of the professions, he followed in his father’s footsteps and was called to the Bar in Gray’s Inn in 1924. Bradley probably never practiced, and a few months later joined the staff of the Library of the University of Liverpool, gaining promotion in 1931 to become the first holder of the post of deputy librarian.((Lionel’s father had been a member of the court of the University since 1921.)) From then until 1936 he was active in the Library Association, contributing to conferences and to the Year’s Work in Librarianship. Then in 1936 Bradley resigned,((According to John Wells, Rude Words: A Discursive History of the London Library (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 175, this was because of an indiscretion with a male undergraduate.)) moved to London, and for four years seems to have spent his time attending and writing about ballet, before he accepted the post of assistant secretary and sub-librarian at the London Library, where he was responsible for a revision of the subject index. This post appears not to have curtailed his attendance at musical events in the years after 1940, as the series of Bulletins attest.

According to the Library Association obituary Bradley ‘could have achieved eminence in librarianship, but music and ballet were his real interests’ and added that:

His friends will remember him as a “wary and acute reasoner” – witty, urbane, the most generous of eccentrics and the most open-handed and forgiving of friends.

Bradley published one book: Sixteen Years of Ballet Rambert (London: Hutchinson, 1946), and contributed to, among others, the magazine Ballet (1939; 1946–52). On 30 December 1953 he wrote up a report on a broadcast concert by the Harvey Phillips String Orchestra, in what proved to be the last of his Bulletins. He failed to turn up for work the following day and was found dead in his flat. According to John Wells,((Op. cit., p. 188.)) if he had lived, Bradley would probably have been appointed in 1954 as successor to Simon Nowell-Smith as Librarian at the London Library.

Fig. 4: Lionel Bradley (c. 1950?). Photo: unidentified photographer (Courtesy of the London Library)

The Bradley Collection at the RCM is not large in terms of shelf-space occupied, but it is varied, and in terms of word count, substantial:

- Notebooks

Opera Casts (9 May 1914 – 20 Oct 1928)

Notes on Concerts and Operas 1923–1926

Notes on Concerts and Operas 1926– [1928] - Bulletins [‘Brief Notes…’] 28 Oct 1936 – 30 Dec 1953

- Lists of broadcasts heard, 04 Sept 1939 – 30 Dec 1953

- Daily calendar for 26 Sep 1937 – 17 June 1939 listing main operatic, ballet, theatre and concert performances, and indicating which Bradley attended

- Press reports relating to music (NOT reviews) under various titles (e.g. Miscellanea Musica), 1951 – 53

- Two lists recording the operas Bradley had heard during his life (top three were Figaro (41), Così (37) and Peter Grimes (29))

- Concert Programmes ((The original donation to the Central Music Library included programmes. It was only during the later stages of the listing of the bulletins at the RCM (from 2008 onwards) that it became apparent that at some earlier date the programmes had simply been interfiled into the main sequence of programmes (ordered by venue and date) at the CPH. As might have been expected, it emerged that Bradley annotated some programmes (most notably with details of encores), and that in any case they sometimes clarified references in the bulletins, so it was decided to locate and keep separate the Bradley programmes, to facilitate cross-referencing with the bulletins; that project was not begun prior to the closure of the CPH.))

Fig. 4a: Lionel Bradley, Brief Notes on Concerts etc 23 May-June 17 1945, p. 1. Holograph: 20 pp., 185 x 122 mm, ink on paper. (Royal College of Music)

It is the Bulletins (as Bradley called them, although they were always headed ‘Brief Notes’) that are of most immediate interest to music historians. Fig. 4 shows the Bulletin that I happened to pick out to read when we opened the box in 2008: its format – with very precise details of date, time, venue, sponsoring organisation, and the main performers for each event – was established fairly early on and maintained throughout the sequence. Bradley’s study may have been untidy (as was reported in The Times obituary) but not his working methods: in this he was true to his profession as a librarian.

Fig. 4b: Lionel Bradley, Brief Notes on Concerts etc 23 May-June 17 1945, p. 20. Holograph: 20 pp., 185 x 122 mm, ink on paper. (Royal College of Music)

The final page of each Bulletin also eventually adopted a fairly standard layout that makes clear that the these documents had a a social purpose: they were not just notes for Bradley’s own personal use but were in fact blogs avant la lettre. They were sent to a small, informal group of friends some of whom he had met in Manchester, Oxford or Liverpool and the members of the group were expected to circulate the bulletin, listing the date they received it, before the last person on the list returned it to Lionel (though he clearly had to send out reminders now and then). All the surviving Bulletins post-date Bradley’s move from Liverpool to London, but initially they did not include circulation lists: whether this indicates that at first they were prepared as Bradley’s own records, or that they were circulated from the start but it was only after some months that Bradley realised that the provision of recipient details would assist with their efficient distribution is not clear. Whatever the case, the bulletin covering 10–28 November 1937 was the first to include the circulation list.((Interesting the parallel Ballet Bulletins, which also commenced in 1936, did not adopt this feature until the 21 April – May 12 1938 issue.)) What is remarkable – and a tribute to both the recipients and the Post Office – is that there are only three lacunae in the sequence: July–September 1938 (probably 2 Bulletins), June–October 1939 (so no comments about the outbreak of war), and May – July 1953 (particularly frustrating since as a result we do not have Bradley’s response to the first performances of Britten’s coronation opera, Gloriana).

The complete list of recipients is

Of the group of four who were on the first circulation list, James Leadbeater Wing (1898–1952) was the oldest and had probably known Bradley the longest, despite the fact that he was born and educated in Sheffield. Both men had been undergraduates at Oxford (c. 1917–22), had shared rooms on High Street, Oxford, and got to know Edward Sackville-West.((Recorded by Bradley in the report for 23 January 1953.)) For much of his career James (‘Jimmy’ to Bradley, ‘Jim’ to his family) was the managing director of the family firm, the steel manufacturers Leadbeater & Scott Limited in Sheffield.((The company was taken over by Imperial Metal Industries in 1968.)) His nephew, Peter, recalls ‘I just remember him as a very gentle man with a love of music and a huge collection of classical records – all the old 78 rpm which he played on a record player with a large horn speaker.’ Wing was also an amateur pianist, and his small grand piano, and part of the horn speaker are both visible in Fig. 5b. His friendship with Bradley was evidently enduring and the bulletins make reference to meetings in London, and in particular a ten- day visit by Wing in October 1948.((See the report for 24 October 1948; in October 1953, a year after James’s early death, Bradley met up with his younger brother, Tom, in London.))

Fig. 5a and 5b. Photographs of J.L. Wing c. 1912 (while a pupil at King Edward VII Grammar School, Sheffield) and, c. 1950, with his mother, Elizabeth Pashley Wing (née Leadbeater, 1874–1957). In the background of 5b the bottom of the horn of his record player is clearly visible. (Reproduced by kind permission of James Wing’s nephew, Peter Wing.) [To view a larger version, click on the image.]

Florence Eda Whelan (26 May 1907–May 1998) was one of Bradley’s colleagues at Liverpool University Library, who retired on 31 July 1967 after more than 42 years of service (so she joined just after Lionel). She was the only member of the group who received all the Concert Bulletins. Given his age, Rex Hillson (1915–2004) must have met Bradley in the late 1920s or early 1930s, perhaps at Hallé concerts. He was trained, but never practiced, as an architect. Instead he entered the family business, the Manchester Slate Company. A passionate music lover – Sibelius, Walton and Britten were among his favourite composers – he was associated with the Hallé Concerts Society for 59 years in a variety of roles until his death. Under the terms of Bradley’s will, Hillson was responsible for the disposal of his friend’s chattels, so it is thanks to him that the concert and ballet bulletins survive. Stanley Meyrick (1913–2002/3), was probably born in West Derby in Liverpool, and perhaps met Bradley at about the same time as Hillson. He too trained as an architect and in later years was active as an amateur actor closely involved with the Barn Theatre, Welwyn Garden City from 1950 until 1990; he was also a director of the Welwyn Festival Association Limited (1984–93). On at least one occasion he met up with Bradley in London.((See the report for 5 August 1942.))

Of the other members of the group rather less information has come to light. By May 1945 W. E. A. (Ted) Lewis was serving as a Pilot Officer with or attached to the Royal Canadian Air Force in Middleton (at that time home to 419 Squadron and 428 Squadron, both flying Lancaster heavy bombers).((His address is given in the bulletins of the period as the Officers’ Mess at the base.)) Chris Cooper was a founding member of the ballet bulletin group (see below), but no background information about him, Mrs Mann or William Hanna has been uncovered. Although Robert Alfred Armstrong Dodds (1906–1961) was the last new member of the group, he clearly knew Bradley well enough to invite him to be his son’s god-father and both were beneficiaries under the terms of Bradley’s will. When Dodds joined in 1948 he was apparently working as a junior school teacher in Enfield before moving to Stockton-on-Tees in 1951,((See the report for 2 September 1951.)) where he died ten years later.

No evidence has come to light that this informal group ever met together, and what evidence there is suggests that only some of its members knew others personally. In the absence of any other traceable correspondence, the extent that the bulletins evoked responses from the recipients also remains unclear. Michael Kennedy’s memories of Rex Hillson suggest that it is rather likely that he wrote to Bradley about musical life in his environs, and perhaps other members of the group did so as well.

The extent of the collection of concert bulletins is impressive:

Number of bulletins: 178

Number of pages of text: 3,358

Estimated word count: 666,000

But it needs to be borne in mind that there were probably at least two more similar series. Bradley’s main interest was dance, and his ballet bulletins are now in the Theatre Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.((This series extended from October 1936 to December 1953. Initially the reports were in the form of continuous narrative prose without any reference to the recipients, but very quickly they adopted the same structured format as the concert bulletins, and from the end of April 1938 the recipients were listed, including Rex Hillson, Stanley Meyrick, Chris Cooper and Edna Whelan.)) Moreover, in the early concert bulletins, until May 1937, Bradley also reported on films and theatre, and the ballet bulletins in October-December 1936 included notes on films seen. So, it seems possible that Bradley continued to report on film and theatre thereafter, in one or two separate series that have not yet been located.

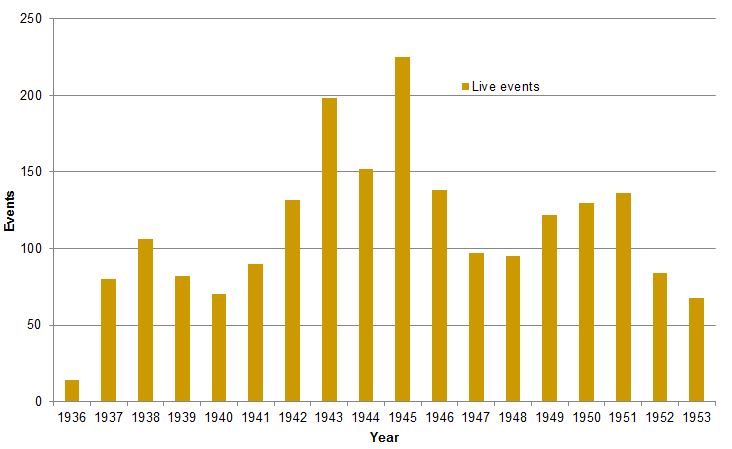

Another measure of Bradley’s diligence is the number of live music events on which he reported:

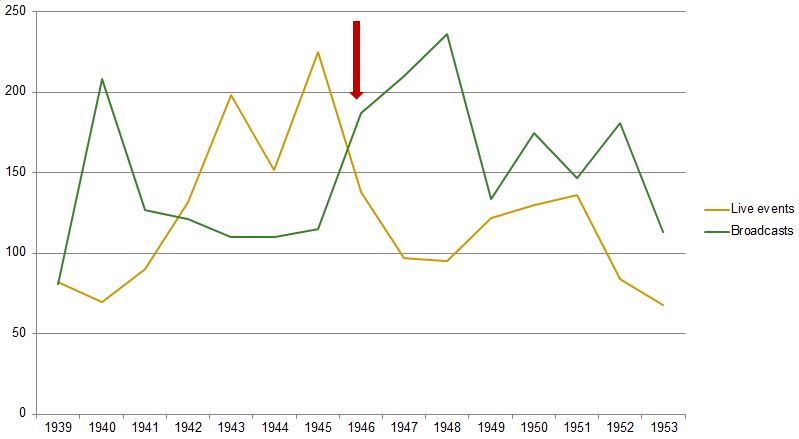

Fig. 6: Chart showing annual totals of live music events reported in Bradley’s concert bulletins, November 1936-December 1953.

However, the bulletins provide only a partial account of Bradley’s experience of music: ballet was reported in a separate series, and the concert bulletins contain no reports of the radio broadcasts he heard before June 1946, nor any systematic references to his listening to his (clearly extensive) record collection.((This collection presumably also passed to Rex Hillson after Bradley’s death. If it survives it has not yet been traced. It is worth noting that James Wing and (according to the late Michael Kennedy) Rex Hillson also had extensive record collections.)) Even so, the number of events (live and broadcast) that are recorded is impressive:

Live events reported in the Bulletins 2773

Broadcasts reported in the Bulletins 754

In addition, Bradley also maintained a private list of the broadcasts he heard from 4 September 1939–30 December 1953,((The starting date for this listing is, of course, highly significant: even Bradley was not oblivious of momentous events in the wider world.)) and a comparison between entries in the two lists during their period of overlap reveals that Bradley was being very selective in what he reported in the Bulletins. So a more accurate figure for the total number of concerts and operas he attended and broadcasts to which he listened is rather higher: 4260.

A graph comparing Bradley’s access to music by different modes of delivery is revealing:

Fig. 7: Graph showing the numbers of live and broadcast music reported in the music bulletins by, 1939-53.

The dramatic rise in radio listening and decline in attendance at live events in 1940 undoubtedly reflects the impact of the blitz and the second temporary closure of theatres (September–November 1940). Bradley may also have found it more difficult to attend live events because he took up his post with the London Library in that year.

Rather more striking is the dramatic increase in Bradley’s radio listening in 1946–7, linked – as he acknowledged – with the start of the Third Programme, an explicitly ‘high-brow’ station, on 29 September 1946 (marked by the red arrow in Fig. 6). The BBC now had a coordinated policy of broadcasting major musical events – exclusively high art – which might be broadcast on the Home Service one night and repeated on the Third Programme the following evening.

The reports deal almost exclusively with music – there is almost nothing directly about politics or the war, though on one or two occasions (both early in the series) Bradley makes comments that are anti-semitic. One example of a note that does touch on political matters concerns a concert by the Berlin Philharmonic:

…I wish, however, that Furtwängler were a more inspired conductor. He seems to lack the ability to thrill….

…I have had the curiosity to compare the list of members of the orchestra with that of 1931 when Henry Holst was the leader. The orchestra on this tour is a little larger & one or two players have changed their places – moving up or down the list, as is likely to happen in any big orchestra over a period of years. And in spite of racial & political exclusions it is largely the same orchestra since of 58 string players of 1931 40 remain and 24 out of 28 wind players.((Bulletin for 2 May 1937: Queen’s Hall. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwängler.))

Whereas Bradley would express a view about Furtwängler’s conducting, his curiosity about the make-up of the orchestra merely results in his tacit acceptance that a quarter of the orchestra has changed since 1931. Nevertheless it is worth observing that his ability to make the comparison at all obviously reflects an efficient personal filing system.

Seven years later there is a rare example of a more direct report on the conflict that in 1937 was not yet generally perceived as inevitable:

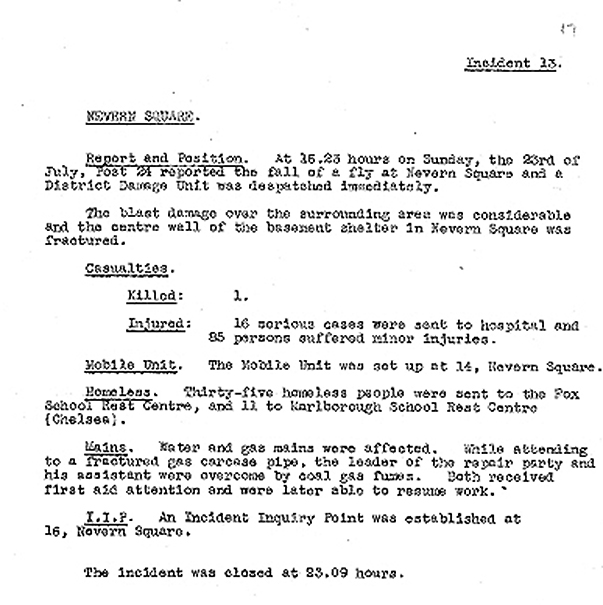

This was the first of a new series of Sunday Concerts designed by CEMA [to] alleviate the present dearth of week-end music….After the interval came Schumann’s Carnaval.

During the playing of ‘Eusebius’, a flying bomb came down at Earls Court a mile & a quarter away, near enough to make all the loose doors etc. of the theatre rattle. It didn’t interrupt the flow of the music or the attention of the audience, Perhaps that is not unreasonable since when one of these things has gone off one knows that it is over & hasn’t to trouble (as with manned bombers) that it may drop another one any moment.((23 July 1944, 3:00 pm, Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith: Myra Hess. It is worth noting that this is the only reference to CEMA in the bulletins.))

The bomb caused quite a lot of damage, but mercifully few casualties:

Fig. 8: Bomb damage report for Nevern Square, London, 23 July 1944. (Nevern Square Society website)

What is more remarkable is that Bradley makes no mention of the fact that on 28 February 1944 a 500lb HE bomb severely damaged the London Library. The staff immediately rallied around and with the younger female staff dangling from the surviving beams, the surviving books were passed down and moved to the basement of the National Gallery for safety. Despite what we might consider the main priority, Bradley left to attend the lunchtime Brahms concert at the Gallery: not the action of a team player.

When it came to performances, Bradley did not always restrict himself to an account of the work and/or its performance, but also commented other aspects of the concert experience. References to venues are by no means uncommon: the acoustics of the RAH are deemed simply impossible for music, but he also has doubts about the suitability of the Queen’s Hall:

The whole concert sounded so ineffective that I began to suspect that I have got a seat which is acoustically bad. I shouldn’t have thought that the 18th row of the stalls was too far back. It is only just beneath the circle & my position to-night corresponded closely with that at the Philharmonic [RPS series] except that I was on the right instead of the left . But that may have made the difference. If only London possessed a concert room like the Free Trade Hall or the Old Liverpool Philharmonic!…((26 October 1938, Queen’s Hall: BBC Symphony Orchestra, Joseph Szigeti, Adrian Boult.))

Bradley also offers occasional sociological comments, as in this note on the audience at a concert for the London Contemporary Music Centre at Cowdray Hall, on 5 October 1937:

This was a very different affair from last night’s [Wigmore Hall concert by the International Quartet]. Cowdray Hall is on the ground floor of some nursing institution [Royal College of Nursing], just of the S.E. corner of Cavendish Square.

It is a pleasant light rectangular room holding about 200 people and was not quite half full. In contrast with most musical audiences this seemed to consist of people who looked both intelligent and happy. There were as many women as men & all ages, though there were not many who looked to be under 30….

However, Bradley was chiefly concerned to report on music and its performance. His tastes were catholic – ranging from early music and the baroque (with some experience of historically informed performance practice) to the avant-garde, e.g. Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. He was opinionated (Dvořák and Bax were two bêtes noires) and discriminating (he found Shostakovich uneven). His knowledge of the canon was considerable, but he was always willing to explore less familiar territory, and was fascinated by new music generally. Of the younger composer’s whose music he encountered, one caught his interest in the 1930s and deepened over the years – Benjamin Britten – and the bulletins allow us to follow Bradley’s evolving appreciation of his work.

When Bradley first heard Britten is not known, but on 25 January 1937 he watched Night Mail (‘superb if rather too long’)((Interestingly Bradley makes no reference to the music or its composer)) in a programme of surrealist and avant-garde films at the Everyman and on 20 June 1938 he heard an ISCM concert that included Britten’s op. 10, a work that did not elicit unequivocal praise:

Boyd Neel himself conducted his orchestra in Benjamin Britten’s Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge (Opus 10). The introduction was particularly interesting and effective and there were 10 variations. Some of these were beautiful and the “aria Italiana” was a brilliant piece of parody but though the work was so good in parts there was, on the whole too much of it. It would probably be more acceptable if 2 or 3 of the less effective sections (the Bourée Classique, the Wiener Waltz & the moto perpetuo) were omitted. The work had a warm reception and was probably the best thing in the first half of the concert.((This might be compared with Bradley’s response to the UK premiere of Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion which ended the concert: ‘This … is difficult music but very rewarding. It should be as interesting 50 years hence as to-day when most of these works will be outmoded and forgotten. At the end, the composer had a real ovation.’ The other composers represented were Guillume Landré, Peggy Glanville-Hicks, F. Bartoš, Knudåge Riisager and Ernst Křenek. ))

Bradley remained of the same opinion when he heard the work again on 2 January 1939. On the other hand, the next work he encountered Les Illuminations (heard on 30 January 1940) made a deeper impression from the start, and his report reveals how important opportunities for rehearing new works were for him, and the role recordings played in the evolution of his musical world:

The [second] work … was a song cycle by Benjamin Britten for soprano & orchestra entitled Les Illuminations (Op. 18) & consisted of some ten prose poems by Arthur Rimbaud. It was a brilliant and convincing piece of work & was brilliantly performed with Sophie Wyss as the soloist. Though I could not distinguish many of the words, some indication of their content was given by the titles. The voice part was always interesting &, I should say, illuminating too & the accompaniment for string orchestra was marvellously varied by the use of pizzicato etc. or by some special prominence given to one section of the orchestra, especially the lower strings. It seemed to me to be a work in which one could go on finding fresh beauties & that there was much more to it than the facility which is so characteristic of this composer. I could wish (tho’ it is doubtless a vain hope) that the whole cycle might be recorded so that it could be studied at leisure & made really familiar.

Despite the absence of any recordings, when Bradley heard the work again, on 8 June 1942, his response to the work was even more positive: ‘I was more than ever convinced of the real inspiration of Britten’s settings & feel that the whole cycle is the most beautiful & interesting new music I have heard for years’. Nevertheless, in the phrase italicised in the passage above Bradley repeats an already well-established critical mantra, and although elsewhere he normally does so to discredit it, it raises the issue of the extent to which his responses are genuinely independent, or in some way influenced by press reviews (some of which he encloses with the bulletins). On the whole it appears that he is relatively independent except for rare occasions when a concert is written up some time after the event.

Bradley again refers to how technology could enhance appreciation of new works when he reporting on the UK premiere of the Violin Concerto on 6 April 1941:

There are 3 movements (directed to be played without a break, tho’ to-day there was a slight pause between the first & second) 1) Moderato con moto, 2) Scherzo-Vivace, ending in a cadenza for the soloist which leads directly into 3) Passacaglia & Andante lento. It is an interesting & stimulating work with some very beautiful passages. I wouldn’t rate it so high as the Bloch concerto or the two by Prokofiev to which there is an obvious debt, but it is a mature work, written without hesitation & vacillation & one with which I would gladly make a fuller acquaintance. But when shall I hear it again? It is to be broadcast on the afternoon of April 28 (a Monday) – how many of us can hear it then? The best hope is that Tom Matthews should record it here or Brosa in U.S.A. – but will they do that in war time…. I should say that the solo part is a very difficult one but T. M. (tho’ like the conductor he had a score in front of him) played it without any lack of confidence, as tho’ he had put all its difficulties behind him & was thoroughly in love with the work…. It is hardly a lyrical work, tho’ the conclusion is serene & peaceful enough but even its extravagances stimulate without shocking. I should say that the performance was a fine one by all concerned.

Bradley’s comparison with Prokofiev (particularly the first concerto) seems apt – although Britten would have disagreed – and the reference to Bloch is characteristic, since Bradley had a very high opinion of his works, the First String Quartet in particular.

It was as a composer that Bradley was aware of Britten, but when he and Pears returned to the United Kingdom in 1942 Bradley responded positively to both a new work and the arrival of two musicians he quickly assessed as of exceptional calibre. Of their Wigmore Hall debut on 23 September 1942 he wrote:

After an interval we had the first (? public) performance of a new song cycle by Benjamin Britten, Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo for tenor voice & piano, sung by Peter Pears with the composer at the piano. These settings … seemed to me very lovely & moving. They were sung in Italian & seemed to have all the lyricism of Italian song writing combined with a feeling for the just accentuation of the words, worthy of Wolf at his best. The accompaniment seemed sometimes rather spare but was of a convincing inevitability. The singer not only had a very beautiful and expressive voice but used it like a first class instrumental virtuoso.

The description of Pears’ singing is striking in that it draws a parallel also employed by Hans Keller: when recalling, in 1951, the impact of hearing Pears for the first time, Keller quoted himself: ‘For once a singer who isn’t a poor substitute for an instrumentalist… within eleven bars, I have become turned from a stern examiner into an admiring pupil.’

Bradley’s appreciation of their gifts as performers was even greater when he next heard them, a month later on 22 October:

This was a very notable recital. I do not think that I have ever heard Schumann’s Dichterliebe more beautifully sung, with just the right sweetness & strength. It was a most moving performance…

The only other item was a repetition of Britten’s Seven sonnets of Michelangelo recently heard at the Wigmore Hall. It is a remarkable work, in the great lyrical tradition & yet very individual. Some of the songs, especially Sonnet 30, are especially lovely. And to-day I appreciated & enjoyed them the more through having taken the trouble to copy out the Italian to read as I listened. But hearing them just after a great masterpiece of song writing, I am not sure that these are, permanently, of the same calibre.

Britten both in the Schumann & in his own song cycle showed himself to be an inspired accompanist. Mr. Pears’s voice & singing deserve the utmost praise that can be bestowed.

The slight doubt about the Sonnet’s themselves seems to have have been short-lived, and in February 1943 Bradley could write: ‘The work itself fills me with more admiration each time I hear it.’

On the other hand, Bradley had more problems with the instrumental works and was not helped by the paucity of performances. The Sinfonia da Requiem failed to arouse any enthusiasm:

[6 December 1942] I heard in the summer a broadcast of the first performance of Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem. I thought it interesting then, but was not so much attracted as by others of his works. Hearing it now, at first “ear”, my attitude remains very much the same. It is clever in its orchestration & perhaps more than that in its feeling, I should like to have more opportunities of hearing it, but I can’t yet say that it really appeals to me. The three movements – Lacrymosa (a sort of solemn funeral march), Dies Irae (an extraordinarily bizarre dance of death) & Requiem Aeternam (the peaceful & beautiful conclusion) – were played with a barely perceptible break between each. It is probably a difficult work but Lambert and the L.P.O. were triumphantly masters of every problem.

In the case of the First String Quartet he was particularly hampered:

[14 March 1942] After some hesitation I decided in favour of this concert [Royal Albert Hall, LPO conducted by Basil Cameron] instead of the concert of modern chamber music at the Wigmore Hall (I had subscription tickets for both) since owing to the recent illness of members of the Griller Quartet, the new Quartets by Britten & Bliss were to be postponed & a performance of the Bloch Quartet given instead – & I have heard them play it twice at the National Gallery in the last few months….

This report is particularly interesting, because it reminds us (or perhaps informs us) that the work was to have been given its UK première in March 1942, but because of illness the Griller Quartet had not been able to prepare the first performance of it or of the Bliss Quartet in B flat. Clearly there had been some difficulty in preparing these two new works – incidentally both commissioned by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge – but whereas the Bliss was heard on the 28 May 1942 at a concert given by the Quartet in the National Gallery series (and was broadcast shortly before, as Bradley noted), the Britten had to wait thirteen months, until 28 April 1943, when the Griller Quartet finally performed it at one of the Boosey & Hawkes Series at the Wigmore Hall. Bradley, like some of the critics, found it a tough nut to crack:

The concert ended with the first performance in England of Britten’s String quartet No. 1 which was published last year & is dedicated to the generous American patroness Mrs. Coolidge. I can’t be sure at one hearing whether it is a really good work & whether I really “liked” it. I can say that I feel it was enough in itself to justify the concert & that I found it as exciting and stimulating as I have done the first hearing of quartets by, say, Malipiero or Bartok. It is a very individual work & obviously goes its own way without setting out to soothe or please. The first movement, Allegro vivo, has a slow introduction (which recurs after the exposition & at the end) consisting of a pizzicato theme on the cello while the other strings play dissonant phrases in the upper register, with harmonics. It sounds weird almost repellent but very vital & prepares for the energetic music which follows. The scherzo, Allegretto con slancio, begins with a staccato theme, ppp., into which each instrument in turn breaks with a ff. phrase. The slow movement, Andante calmo, is, naturally, less violent & has some fine solo passages. The last movement, Molto vivace, is very lively & works up to an effective climax. The work had a very cordial reception, tho’ not quite so enthusiastic as that for the Michelangelo Sonnets.

One wonders whether the Grillers had a similar difficulty with the work: compared with the Bliss it is strikingly innovative in its re-conceptualisation of quartet textures, technically demanding (particularly the very opening and similar explorations of extremely high tessitura) and harmonically astringent. Whereas the Bliss was recorded by the Grillers in March/May 1943 it seems it was not until the early LP era that the Britten was recorded by the Galimir Quartet in America.

When Bradley heard the Quartet for a second time, albeit in less than ideal conditions at a National Gallery concert on 28 May 1943, it made more sense:

It was very good to be allowed to hear Britten’s S.Q. No. 1 again so soon, only a month after its first English performance. It is so individual & subtle a work that it was not easy to take it all in from a position on the fringe of a vast audience with its involuntary distracting noises, but I was enthralled throughout & felt that I appreciated its inner logic better than when it was quite new to me. From its astonishing opening with a strong pizzicato theme on the cello over a background of perilously high & unexpected chords, it goes its own way, strange but alluring, & always intensely vital. I felt that the second movement, allegretto con slancio, was almost too succinct – the whole work is on the short side – & tho’ it does not affect me profoundly as the Bloch Quartet does at its best, it is as stimulating as any work I know.

In part Bradley’s more positive response may have been a result of a more accomplished performance, by the Zorian Quartet, described by him as ‘at their very best, unequalled in this country & probably not excelled anywhere’.

Bradley continued to listen and re-listen to Britten’s music, so it is hardly surprising that on 31 May 1945 he went to the Wigmore Hall to hear the ‘Concert Introduction to Peter Grimes’:

This was an interesting occasion but it would hardly be profitable to describe it in detail. Proceedings began with a general introduction by Tyrone Guthrie on Sadlers Wells & English Opera & the genesis of the new work. Then the producer, Eric Crozier, gave an outline of the opera illustrated by characteristic excerpts for the leading characters & the chief minor ones (without chorus) sung by those who will take these roles in the opera to the composer’s own accompaniment on a piano. It is difficult to judge its character in this form – it hasn’t the excitement of ‘Les Illuminations’ or the sheer beauty of the ‘Serenade’ but it will doubtless sound very different in the theatre. We were given only a very short passage between ‘Peter Grimes’ (Peter Pears) & the schoolmistress (Joan Cross) who befriends him. The plot seems somewhat complicated, but probably in action the minor roles will fall into place in the background, providing connecting links, local colour & dramatic excitement. I was sometimes reminded of Ethel Smyth’s “Bosun’s Mate” but that is not surprising since in this opera, too, a village landlady (Edith Coates) is one of the main characters & the scene is a small fishing town & Crabbe, on whose poem, “The Borough”, Montagu Slater’s libretto has been based, was a realist describing the daily life of his time, “in all its meanness and familiarity”. So there are no romantic scenes or heroic situations but action & people are set in a homelier native background.

The report on the first night of Peter Grimes, on 7 June 1945, is one of the longest in the bulletins, itself evidence of the impact the work made on Bradley, and his recognition of its importance:

…The concert introduction had served a useful purpose by giving us a general outline of the plot & making us familiar with the characters, major & minor. But it hadn’t really at all prepared us for the sort of opera we were to experience & by allowing each of the characters to sing one characteristic passage had put the whole thing rather out of focus, by treating each character alike, without regard to his or her relative importance. In general I think I can say that while there are features in the opera which I don’t like & certain things which will fall better into place, as I become familiar with the work, I am convinced that it is a work of genius – not without blemish, but with passages of extraordinary beauty & effectiveness….

At the concert introduction the music was played on a piano which gave very little idea of its character. Heard in full it proves to be the finest of all Britten’s scores to date. … [T]he whole score is full of richness, striking effects such as one expects from the composer, yet always apt to the moment & marked by that inevitability which usually accompanies his most daring inventions. I wished sometimes that the vocal writing were easier to the voice & the ear. It is often difficult to distinguish any words at all… &, to give one instance, I rather question the need of giving Joan Cross a vocal line which taxed her fine voice to the uttermost. Ellen Orford is not a Turandot & some of the difficulties seemed unnecessary & ineffective. The performance was very good indeed. Some passages were simply magical in their beauty & impressiveness. But it was not until the second act that I was completely won over & convinced that I was probably listening to a masterpiece….

If for Bradley there were aspects of the music that did not entirely convince him, the mise-en-scène clearly impressed him:

The production is, I should say, as good as the famous Wells production of Boris & Eric Crozier deserves the greatest praise for his subtle & imaginative production. The effect is completed by Kenneth Green’s excellent scenery and costumes which have all the fascination of a series of old prints. – the early nineteenth century with its curly brimmed hats for the men & bonnets for the women, the variety of colour (men’s normal clothing had not yet become sombre) & the colourful attire of the fisherfolk all made for good pictorial effects. It is a detailed, realistic setting, but it is set off by very good lighting, so that it never becomes distracting.

A second hearing (15 June) encouraged Bradley to identify a few more negative responses, and to be more specific about the passages that impressed him most:

Peter Grimes impressed me even more at second hearing.…I still find in the opera somewhat too great an admixture of styles. At the beginning of the 3rd Act I felt conscious of reminiscences, in turn, of “Fledermaus”, “Trovatore” and “Rigoletto”, if not indeed of Gilbert & Sullivan & I do not think the cutting out of the scene in which Swallow drunkenly tries to catch one of the Landlady’s two “Nieces” would be any great loss, tho’ it has one of the most catchy tunes of the opera (there is little, on the whole, for the Butcher Boy to whistle on his rounds). But the fine moments predominate – the quiet scene between Peter & Ellen Orford after the inquest, the lovely scene at the beginning of act II when Ellen talks first to the boy & then to Peter while the church service is in progress, the passage in the Hut scene when Grimes first begins to show signs of madness, the eerie effect of the voices of people searching for Grimes calling out his name in the distance and all the incidents at the beginning of the last scene that lead up to his suicide. It is a very fine work & should be the precursor of even finer operas to follow.

The reservation about vocal writing persists in his initial reports on the next two operas, and, significantly these concerns usually focus around the soprano roles:

[Albert Herring, 8 October 1947] The opera …varies from high comedy to farce. There are many nice touches, which will doubtless become more apparent as one gets to know it better. But Britten is sometimes unkind to the voices and, after hearing the opera twice, I feel that there are too few passages which have any tune in them that is likely to become memorable. I don’t think that it is so successful as Lucretia (if comparison is possible) & Lucretia tho’ a very beautiful work is not perhaps so masterly or striking as Peter Grimes. Oddly enough the limited orchestra, with its small compliment of strings compared with the wind, seems to have the effect of drowning the voices at times. It was a daring experiment to produce such a work at Covent Garden & I gather form the critics that this effect of the voices being obliterated by the orchestra was by some acoustical freak more apparent here than at Glyndebourne… I may change my opinion of it, by the end of next week. Britten conducted on both occasions & had a great reception.

Bradley’s prediction proved to be right. Ten days later he wrote:

[Albert Herring, 18 October 1947] I enjoyed this performance, even more than the other three & am prepared to eat my words in regard to my first impressions. I wouldn’t now say that this is inferior to the other two operas – or not necessarily. The trouble with all of them, may be, is that the libretto is not good enough for perfection. But as that of Lucretia has been immensely improved by revision the same may be true of Herring by next year. Peter Grimes is the most stirring of the three & one feels a genuine belief & interest in the characters. Lucretia, tho’ I feel no interest in the characters at all, is in some ways even more beautiful & the final tragedy overwhelms me. Herring is so rich in comedy that one can forgive all the incredibilities. And in all of them Britten, tho’ often unkind to his voices, shows the utmost technical skill & resource – he has a Mozartian facility & a nearly Mozartian sense of characterization. Ernest Newman may complain of their faults as he will, but is there any other English composer (even Vaughan Williams) who has produced three operas which one is glad to go on hearing again & again?

However the process of developing understanding and admiration after repeated hearings is not always the trajectory:

[Spring Symphony, 9 March 1950 (UK premiere)] Even more than Mahler, Britten uses a large orchestra not to produce but for the sake of volume but of consummately varied tone colours & here, as so often, he has been inspired by English poetry to effects which when heard seem as inevitable as they are unexpected… But the general effect is of joy & gaiety and as I went home I said to myself I haven’t heard any new music for some time which has made me feel so happy.

[Spring Symphony, 28 May 1952] Hearing it only once or twice a year since it came out, nearly 3 years ago, I still find it rather an odd mixture & have [not] yet acquired the better sort of familiarity with it which produces not contempt but added satisfaction.

Some works, like the Donne Sonnets, he simply found difficult, and he never achieved complete engagement with them; interestingly he writes nothing about the broadcast of the first performance of Lachrymae (20 June 1950), a similarly austere work. Other pieces, though, he found unlikable or uninteresting:

[Charm of Lullabies, 8 February 1949] The first vocal item was Britten’s Charm of Lullabies sung by Nancy Evans with Norman Franklin at the piano. This consists of a series of 5 lullabies, settings of poems by Blake, Burns, Robert Greene, Thomas Randolph & John Philip. I am sorry to say that they made practically no impression on me. They were pleasant & well sung but that was all – disappointing when I remember the excitement I have had from most other Britten first performances (Illuminations, Michelangelo, Serenade, Holy Sonnets – to name only the solo vocal works). Perhaps the unvarying mood of tranquillity conceals subtleties which are not apparent at first hearing – or did they send me to sleep?

Sometimes a report will contain surprising details:

[Peter Grimes, 01 December 1949] Tonight’s performance had two newcomers & one unexplained disappearance…. The “disappearance” was of one of the nieces (presumably due to an attack of illness). Both were there in Act I but afterwards there was only one so that the female quartet at the end of II (“From the Gutter”) became a trio & Swallow in III 1 (“Assign your prettiness to me”) had only one bird to pursue. This was disconcerting to anyone familiar with the opera but probably passed unnoticed by the others.

Although the report on Britten’s coronation opera seem not to survive, Bradley’s reports on his Festival of Britain opera do. He missed the first performance because of illness, but heard broadcasts, and when he finally saw it in December 1951, it made a deep impact and inspired some of his most perceptive comments about a new work, and also about the performers,

Hearing an opera directly is very much better than hearing it by the wireless, even from the point of view of sound – when the visual effect is added, too, there is no comparison between the two experiences. Yet there is some loss. For on the two occasions when I heard a broadcast of the whole opera and the third when I heard most of Acts I and II, I had the libretto in front of me and therefore did not miss any of the words. In the Opera House, unless one knows the libretto by heart, some of the words are bound to be less clear and some voices are helped by the microphone. In particular Peter Pears, fine as he sounded in the confined space of the scenes in his cabin where the scenery perhaps acted as a resonator, did not seem to have quite so powerful a voice as was needed when he stood on the quarter deck with vast space all round him and only the cyclorama behind. …

I must say that even in the theatre I found the first act a little slow. It is a necessary introduction for setting the situation and bringing the various characters to our notice, but I feel it is rather too detailed and diffused, and might be shortened and concentrated with advantage… But even in this first act there are many good points – Claggart’s brutal directness in questioning the recruit, the haunting quality of the refrain “O, heave, O heave away, heave” and the plaintive quality of the oboe which accompanies the Novice’s lament for his flogging (and is used afterwards as a leitmotiv when the Novice is mentioned or appears) – it has somewhat the same feeling as the cor anglais melody which accompanies the last entrance of Lucretia in “The Rape of Lucretia.”

But with the first scene of Act II the opera comes suddenly to life, helped by the more confined space of the captain’s cabin and the concentration of interest on three characters who now seem to be real persons and not just figures in a nautical pageant. The duet of the two officers (Geraint Evans and Harvey Alan) “Don’t like the French” seemed much more effective when one could see as well as hear them and their contrast with the philosophical Captain Vere (Pears) whose knowledge and mind went beyond theirs was all the clearer….

I don’t feel that this is quite so striking a work as “Peter Grimes” but I am sure it is a major work. The accusation that there are no tunes is palpably absurd (think of Heave, O heave away, heave – the Novice’s lament – Don’t like the French – the Shanty – Claggart’s soliloquy – and Billy’s soliloquy) but it is often true with Britten (it was so in “Peter Grimes”) that the “tunes” become much more apparent as they become familiar. The Prologue and Epilogue make a perfect frame to what is an exercise in philosophy as well as a story of vigorous action. Britten uses his orchestra with characteristic resource and is always careful (he conducted himself to-night) never to let it drown anything essential in the voice parts.

If Lionel Bradley’s bulletins chronicle with particular richness the war-time and post-war emergence of Britten as a major figure, they also contain a cornucopia of reflections on an wide range of other composers of the European classical tradition. Nevertheless, there are limitations or grounds for disappointment:

- If a programme or performance doesn’t interest him the report will be perfunctory.

- The reports deal almost exclusively about music – almost nothing directly about politics or everyday life though occasionally Bradley will comment of the venue, its acoustics or facilities, on the audience (age, size, response), or the experience of concert going.

- Even when Bradley has strong views about a work or performer he infrequently attempts to analyse the basis for his judgments, and it is only rarely in technical terms when he does.

- Bradley had a relatively poor musical memory – he simply forgot works that he had already heard several times, one notable example being Tippett’s Second String Quartet.

On the other hand, the strengths are considerable:

- Bradley is honest about the external factors that influence his listening (tiredness, distractions) and his need to get to know works through repeated hearings. His commentaries also offer insight into how a non-professional, ‘unlearned music lover’ as he describes himself, hears unfamiliar works, and is happy to record his changing assessments of works (e.g. Brahms) and performers (e.g. Clifford Curzon).

- Bradley’s visual memory is far stronger than his aural memory: he is able to recall the details of stage and costume design and stage movement: so he records the changes made during the run of an opera (e.g. Boris Gudonov at the Royal Opera House in 1948) or compares two productions (e.g. Peter Grimes 1945 (Sadlers Wells) and 1947 (Royal Opera House)) in great detail.

- Bradley clearly believes that the experience of music (and, one supposes, art in general) has the power to be life-changing, and he captures the excitement of discovering a previously unknown work that has that power.

The commentary of the first production of Grimes is one expression of that last aspect of his reporting; another was provided by the first UK performance of Britten’s Spring Symphony. Interestingly, in his report on his first (and only) live experience of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (by a semi-professional orchestra under Norman del Mar on 31 May 1949) Bradley makes it clear that for him this life-enhancing power can make itself felt through an imperfect performance, enabling him to revise and deepen his appreciation of a work with which he had not previously connected:((Indeed, in the report for 24 October 1945 he admitted that he had listened to his recording of the work (it must have been the 1938 live recording under Bruno Walter) only 4 times since acquiring it ten years before, and commented that “the first 3 movements seem to me markedly inferior to ‘Das Lied von der Erde’ which they often recall.))

It was of course the marvelous ‘Adagio’, long & very slow, which was the crowning glory. .. There may have been errors of judgement in the performance or actual faults – but they did not matter. This was a real performance of what I must now regard as a truly great work & I feel positively uplifted & at peace by having heard it.

The extraordinary extent to which the arts, particularly the performing arts, preoccupied Lionel Bradley’s life is made clear in a note at the end of the last bulletin for 1952:

I have been adding up my totals of visits to various kinds of entertainment & the result is thus (with 1951 figures in brackets)

Concerts 37 (46½) Opera 43½ (73) 115 Ballet (93+) Theatres 54½ (42) Films 25 (16).

I should have said that my going out has been slightly less interrupted by illness than in 1951 so that the decline in opera & concerts is the more remarkable, except that in the year just ended there was no Festival of Britain & no English Opera Group. The increase in Theatre (& Film) is notable for the dancing items this year (Bali 3, Bip [?] 2, Indian, Slavonic & Kur[destan?]) are balanced by 7 lots of Spanish Dancing in 1951. Am I becoming more intellectual?! It may be worthwhile to add that in 1952 I have actually read 67 novels and autobiographies a category which has not exceeded 40 in any other year since 1930.

Yet, despite the half a million or more words Bradley himself remains elusive: the Bulletins offer only oblique insights into his life and personality. To finally get a brief glimpse of Lionel himself we have to turn to an amused, affectionate and poignant memoir by a fellow ballet fanatic, Richard Buckle, writing in The Times, a few days after Bradley died peacefully in his sleep:

Everything he saw or heard he wrote down: and everything anybody else wrote …he found mistakes in and wrote to them about. He brought fault-finding to a fine art, and was always so kind and amused about it.

I think of him, stout, bearded, quiet, shy, but twinkling behind his spectacles, going every day from his flat in South Kensington to his work at the London Library. I think of him hastening slowly home or to Covent Garden at the end of a busy day. But his day really only began after dark; and my most characteristic picture of him would show him seated in the untidy study after an excellent dinner cooked by the devoted Mrs. Whitman with a glass of brandy beside him, surrounded by piles of books, listening to Mozart. When one left him he would be looking things up and writing letters until three in the morning.

He had many friends among dancers – they used to call him “Uncle Leo” – but I think he was rather lonely.

Buckle was probably right: in a report on a broadcast concert of orchestral music by Stravinsky, Ibert, Van Dieren, Schoenberg and Fauré on 9 March 1952 Bradley expressed regret that he had no-one with whom ‘to share the musical pleasures … quite apart from my adventures into modernity’. Apparently the bulletins were an only partially successful attempt to fill this gap in Bradley’s life, but thanks to them we have a unusual and valuable contemporary perspective on British musical life in the mid-twentieth century. His Ballet Bulletins have been known and used by dance researchers for at least two decades: the Concert and Opera Bulletins perhaps now deserve their moment in the limelight.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank a number of individuals for their generous help and scholarly support:

David Allen (Royal Society of Chemistry)

Joan Bailey (London Library)

Paul Collen (RCM)

Oliver Davies (RCM)

Robert Gill (Barn Theatre)

Dr Katy Hamilton (RCM)

Martin Kay (University of Liverpool Library)

Michael Kennedy

Inez Lynn (London Library)

Rachel Neale (Manchester Grammar School)

Jane Pritchard (V&A Museum, Theatre Collection)

Bruce Ramell

Michael Riordan (Archivist, St John’s and the Queen’s Colleges, Oxford)

Stuart Robinson (Hallé Orchestra)

Doug Summers

Jonathan Summers (British Library)

Ruth Walters (Westminster Music Library)

Jeremy Ward (Manchester Grammar School)

Peter Wing

The quotations from the Concert Bulletins are reproduced by kind permission of Christine Angel.

[This essay is based on two papers: Britten’s progress 1937-45: a view from the stalls (Britten in Context, Liverpool Hope University, June 2010) and One Man’s Britten: the Lionel Bradley Collection at the RCM (Grove Forum, Royal College of Music, 2013).]

This website by Paul Banks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]()

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

Printing and footnotes

If you wish to print this essay, the print function in your browser should provide a satisfactory version except that, because of the plugin I am using to generate the online footnotes, these will be printed not at the end but in the text within double parentheses.