This informal commentary is the the result of coincidence. Since my wife, Chris, was due to give a presentation at a meeting of an international organisation in Helsinki, we decided to arrive a few days early for a brief holiday, and I realised that while Chris was at the conference I could usefully use the time to try to clarify some details of the early dissemination of Mahler’s music, more specifically the first two complete performances of a Mahler Symphony in Finland.

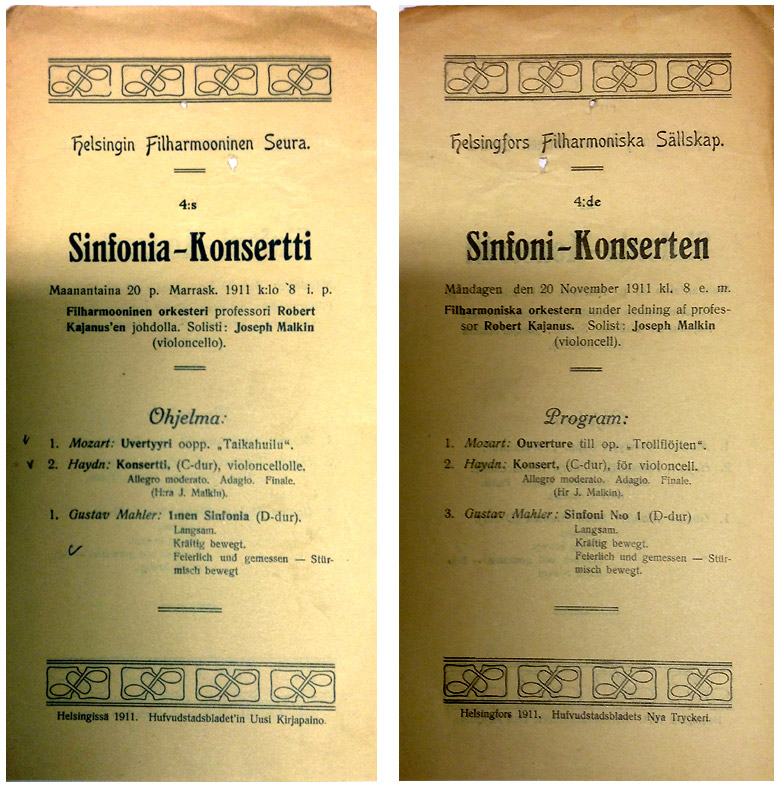

One of my on-going projects is the documentation of early performances of Mahler’s music up to 1914, and a brief report by Axel von Kothen in Die Musik (2. Februarheft 1911) alerted me to to fact that Robert Kajanus (1856–1933) had conducted a performance of the First Symphony by the Helsinki Philharmonic Society Orchestra, probably in late 1911. Unfortunately no further details were included, but colleagues at the orchestra were very helpful and provided a link to their spreadsheet listing what they know of the orchestra’s performance history: this provided a programme for the whole concert, given on 20 November 1911, but it also revealed that on 26 November, Kajanus and the orchestra gave a second performance.1This can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet or CSV file from Helsinki Region Infoshare (hereafter referred to as HPO data). What was striking was that while the first was given at the historically significant Yliopiston juhlasali, the University Great Hall at which many premieres of Sibelius’s music had been heard, the second was listed on the spreadsheet as taking place at ‘Kansantalo’. What was this venue? An initial internet search was not very revealing, but did turn up a picture of the building in which the hall was probably located.

Although I had made arrangements to visit the Helsinki City Archives which hold the historical programmes of the Helsinki Philharmonic, I had not thought much more about the concert or its location until Chris and I were walking around the inlet, Eläintarhanlahti, on the banks of which the conference centre where she was due to speak and where we were staying, was located. After a while we stopped to look back across the water and to my astonishment I realised I was looking at the buildings on the postcard: the modern Paasitorni Conference centre was the ‘Tyoväentalo’ on the left of the postcard. My curiosity was now piqued, and what follows is a preliminary account of the small windows onto Finnish musical and social history that opened up, a narrative that is necessarily open-ended.2 I must thank Pekka Hahle of the Helsinki City Archives for his help in locating relevant material in the archives and alerting me to other research resources, including the invaluable digitisation of Finnish newspapers (up to the end of 1910) by the National Library of Finland.

Mahler’s links with Finland were not extensive and developed only in the last decade of his life, despite the fact that he worked in Hamburg – a town with strong commercial and trading links with Finland – for six years (1891–97): although during the summer of his arrival in Hamburg he spent much of his vacation as a tourist in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, the trip did not extend as far as Finland. On the other side, at least as far as the Finnish press was concerned, Mahler only attracted attention when he was appointed Director of the Court Opera in Vienna: from then on his activities as a conductor, producer and as a composer, were reported in the Finnish newspapers. Nevertheless, there was no surge of local musicians wishing to perform Mahler’s music, and the earliest performances I have traced were of two of the finest early Wunderhorn settings, ‘Nicht Wiedersehen’ and ‘Zu Strassburg auf der Schanz’ (from Lieder und Gesänge, vol. 3), given by the eminent bass-baritone Abraham Ojanperä (1856–1916) on 7 December 1906 as part of a chamber concert in the Helsinki Music Institute Subscription Series;3The programme was published in Hufvudstadsbladet, (05.12.1906); reviews appeared in Hufvudstadsbladet, Nya Pressen and Uusi Suometar. there appear to have been no further performances of Mahler’s music prior to his well-known visit to Helsinki in the autumn of 1907.

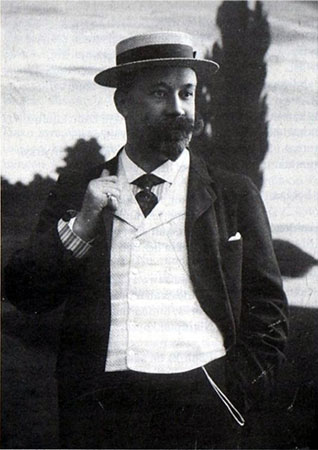

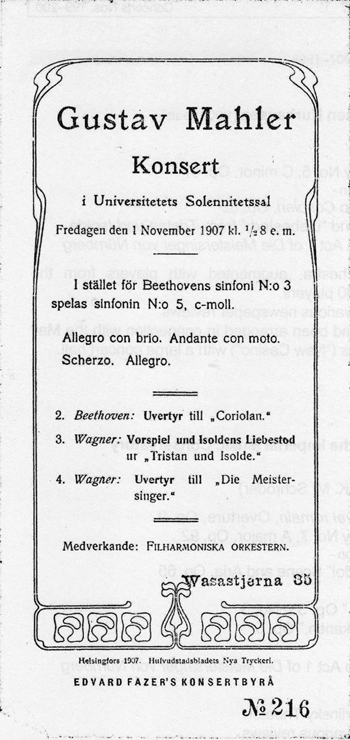

By this time Mahler was at a turning point in his life. He had decided to resign as Director of the Court Opera earlier in the year, on 12 July his daughter, Putzi, had died at Maiernigg and he had been diagnosed with ‘mitral incompetence’ and warned to avoid too much exercise. His visit to Helsinki formed one element in an extended tour lasting from 19 October to 12 November to the Russian empire (within which, from 1809–1917, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy). It was his last such journey while Director and it has been comprehensively documented by Henry-Louis de La Grange.4See H.-L. de La Grange, Gustav Mahler, vol. 3 (Oxford: OUP, 1999), 739–767. On this trip Mahler conducted twice in St Petersburg, and once in Helsinki (1 November), but he performed his own music (the Fifth Symphony) only in St Petersburg (on 9 November). However, if the visit to Helsinki did not directly contribute to the dissemination of his works in Finland, it offered Mahler an opportunity for personal and musical contacts. He not only met Sibelius more than once, but also the conductor and composer Robert Kajanus, with whom he got on rather well, and who he heard perform works by Sibelius (Valse triste and Vårsång, op. 16) and Josef Suk (Fantastické scherzo, op. 25); he was also able renew the acquaintance of the artist, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931). They had first met in early 1904, at the time of the Nineteenth Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, at which Gallen-Kallela had a number of works on display, and were presumably introduced by either Carl Moll (Mahler’s father-in-law) or Alfred Roller (Head of Stage Design at the Court Opera), both of whom, as members of the Secession, were in correspondence with their Finnish colleague. In turn, it was through Gallen-Kallela that Mahler met in Helsinki the architect Eliel Saarinen (1873–1950) and visited Hvitträsk, the house – ‘more a castle really’, according to Mahler – built by Saarinen with his two partners, Herman Gesellius, and Armas Lindgren. Interestingly Mahler immediately made comparisons with Viennese architectural trends, describing it as ‘very much à la [Josef] Hoffmann … like a Finnish Hohe Warte’.

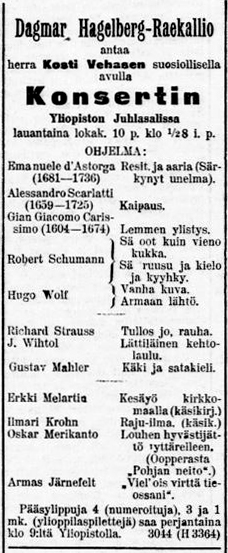

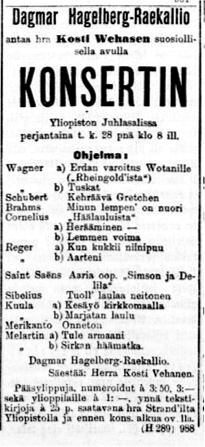

Although Mahler had not promoted his own music, his brief visit attracted an enormous amount of press coverage, and ensured that his career continued to attract attention in Finland even after his departure from his preeminent position in Vienna. So it was an, at the time relatively little-known singer, with (apparently) only one Mahler song in her repertoire, who introduced Mahler’s music to wider musical circles within and beyond the capital. Dagmar Hagelberg-Raekallio (née Sarlin; 1871–1948) was born in the small central Finnish town of Viitasaari, was trained as a singer in Viborg/Viipuri and Paris, but seems not to have developed any significant public performing career until her thirties. In the event this was relatively short-lived as a thyroid operation damaged her vocal chords.5See the Wikipedia article, the Sarlin family webpages (Finnish and Swedish only) which include a memoir by her grandson Yrjö Raekallio, and her auotobiography, Kaiu Suomen laulu. Laulajattaren muistelmia (Helsinki 1934). I am most grateful to Erja Saraste for her help in the preparation of my article and information about the Sarlin family. Nevertheless, Hagelberg-Raekallio deserves a secure place in Finnish performance history for having been perhaps the first singer to perform foreign-language songs in Finnish, a controversial strategy in a bilingual country. The aim was ostensibly to promote a better understanding of the text among listeners who were unfamiliar with French, Italian or German, but inevitably the practice invited accusations of nationalism. Hagelberg-Raekallio’s concert in Helsinki on 16 November 1907 adopted this strategy, with translations of songs by Schubert, Mendelssohn and Chopin appearing alongside Finnish songs, but comprehensive details of the programme seem not to have been published in the press. However an advertisement for a concert given in January 1908 was printed:

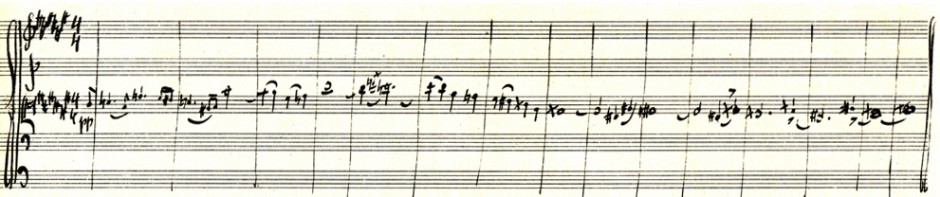

One immediately notes the conjunction of ‘Finnish’ and ‘Folk/People’s’ (suomenkielisen Kansankoncertin) in the description of the concert, and that here a pattern begins to emerge: European song, in translation and broadly chronological order, followed by a group of modern Finnish songs. But this is a short programme, perhaps the result of the paucity of convincing singing translations, and one wonders whether the pianist Bertha Funtek, provided some instrumental interludes. However, by the autumn a stable programme based on the above pattern had emerged that incoporated the one Mahler song, ‘Lob des hohen Verstands’ from the Lieder aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn‘, that Hagelberg-Raekallio regularly included in her recitals:

This repertoire formed the basis of a series of at least twelve concerts that Hagelberg-Raekallio and Kosti Wehanen gave between 10 October–22 November 1908, including performances in provincial centres such as Tampere, Kotka, Hamina, Lahti, Forssa, Turku, Paimio and Jyväskylä. Some of the art songs (though perhaps not the Mahler6So far I have not been able to locate details of the programmes given at Kotka and Paimio. Hagelberg-Raekallio performed the Mahler song in later recitals, including one in St Petersburg in February 1909 (possibly the first public performance of a Mahler song in Russia) and those in Oulu, Raahe, Kokkola, Vaasa and Helsinki in January 1910: I am most grateful to Michael Bosworth, whose painstaking research located these later performances, for this information.) were sometimes replaced by Finnish and Russian folksongs at the end, and the possibility that Wehanen contributed piano solos cannot be excluded.7Kosti Wehanen (1887–1957) was only nineteen at the time, but was to have a distinguished career as both soloist and particularly as an accompanist; he continued to work with Hagelberg-Raekallio until at least 1911. Adverts for all these concerts may be located through the Finnish National Library website.

Apart from this series Hagelberg-Raekallio continued giving solo recitals or contributing to other concerts, and at the end of the year applied for, and was subsequently awarded, a four-month state stipend to study new German song in Cologne, Dresden and Leipzig and Italian vocal teaching in Milan and Rome.8 See Suomalainen Kansa 1906/292 (17.12.1908), 6 and Suomalainen Wirallinen Lehti 1909/9 (13.01.1909), 1. Hagelberg-Raekallio had received a similar grant for her studies in Paris, 1902–3; after her second study trip she was back in Helsinki by mid June 1909, and began advertising as a singing teacher in the autumn. On her return her programmes indeed reflected her exploration of new German opera and song and included Wagner, Cornelius, Brahms and Reger, but at the same time the advertisements imply that her choice of language when performing in Finland remained unaffected; on the other hand, Hagelberg-Raekallio’s concert in Budapest on 12 December 1911 included a new Mahler item – ‘Ablösung im Sommer’ – and, moreover, all the German numbers were apparently sung in their original language, a pragmatic choice since, whatever the theoretical links between Finnish and Hungarian, the Budapest audience would have had a better chance of understanding German songs sung in the original language. On Hagelberg-Raekallio’s return to Finland later that month the preview of her concert at Turku on 19 December recorded that she had already given eighty concerts in her homeland. 9See Uusi Aura, 19.12.1911, p. 5.

If three of his Lieder had reached a rather modest Finnish audience, by mid-1908 Mahler’s symphonies remained completely unknown in Finland – except by reputation and possibly from the study of scores or the piano duet arrangements. Then in October 1908 the programme for the new season of the „Wiipuri Musiikin Ystäwien” orchesteri [Orchestra of the Viipuri/Vyborg Friends of Music] was published, and included in the ‘modern’ fourth programme (alongside Liszt, Weingartner and Wagner), the second movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony.10Wiipuri 1908/226 (01.10.1908), 4. The conductor at the time was the distinguished composer Erkki Melartin (1875–1937), and he was probably one of the relatively few Finnish musicians who had a detailed first-hand knowledge of Mahler’s interpretations and his music because he had studied with Mahler’s harmony teacher at the Vienna Conservatoire, Robert Fuchs, in the years 1899–1901, and so could have heard Mahler in the opera house and the concert hall. Nonetheless he may not have arrived in time to hear the Vienna premiere of the Second Symphony on 9th April 1899.

The Viipuri performance was given on 21 January 1909 as planned and was clearly a success, so much so that by popular demand the movement was also included in the orchestra’s tenth popular concert a week later, on 28 January. Yet despite this encouraging response, and his evident interest in Mahler’s music Melartin did not follow up with further performances of his works during his remaining seasons with the orchestra (up to 1911). So the Viipuri performance of one symphonic movement seemed in danger of remaining an isolated event, and one has to wonder whether, ironically, it was Mahler’s death in May 1911 that finally galvanised Helsinki organisations to look at this an other works. The first response was the national première of Mahler’s Second Symphony given on 30 October 1911 at the Helsingin Musiikkiopisto (Helsinki Music Institute) in Hermann Behn’s arrangement for two pianos, four hands, by Leo Funtek (1885–1965) and Paul van Katwijk (1885–1974) with Alexandra Ahnger (1859–1940) as the contralto soloist. The audience was probably limited in size, and the critical response was mixed, 11See Nya Pressen, 31.10.1911, 5 and Hufudstadsbladet, 31.10.1911, 7. so its impact was probably modest. In any case it was followed less than a month later by an event of rather higher profile, a performance of the First Symphony by what was probably the best orchestra in Finland.

The Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra had it origins in the Helsinkin Orkesteriyhdistys / Helsingfors Orkesterförening [Helsinki Orchestral Association], founded in 1882 by Robert Kajanus, and conducted by him under different names, until fifty years later. Initially it consisted of only thirty six players, growing to forty five in 1895, the year in which its name was changed to Filharmoninen Seura / Filharmoniska Sällskapet [Philharmonic Society]. At the outset it had two main strands to its activity. The culturally prestigious series of about eight symphony concerts per season were, appropriately enough, given in the main hall of Helsinki University, but the much more numerous and relatively informal popular concerts of mainly light music were initially presented in the ballroom of a large hotel, Seurahuone / Societetshuset, over-looking the harbour.12The Helsinki Museum metadata describes the event depicted in Fig 11 as a Kansan-Konsertti (Peoples’ Concert). It is not quite clear what the source for this information might be, but if it is associated with the drawing, then it might be noted that this title was adopted for an important series of concerts by the orchestra that commenced in the autumn of 1888: this would explain the motivation of this sketch, which presumably represents one of the three such concerts given before the end of the year.

Fig. 11: Kansan-Konsertti, Hotelli Seurahuoneen juhlasalissa. Helsingin Orkesteriyhdistyksen orkesteria, Robert Kajanus, 1888. (Helsinki City Museum)

Then in 1889 the Helppotajuinen Konsertti (Popular concerts) and the less frequent Kansan-Konsertti (Peoples’ concerts) transferred to the Great Hall of the newly opened Palokunnantalo (Fire Brigade Building) for a couple years,13To English readers this may seem strange, but the service was not wholly run by municipalities and voluntary organisations maintained their own brigades. Their buildings often included large halls that could be used to generate income. I’m gratefully to Pekka Hahle for this background information. though by early 1892 the majority were again performed at the hotel.14During the next ten years the two series moved in tandem between the two venues until 1904 when the People’s concerts moved first to Palokunnantalo and then, in 1907, to the main hall of the University (the Popular concerts remained meanwhile at Seurahone). The motivations for these moves are not immediately apparent.

Fig. 12: Palokunnantalo (Fire Brigade Building), main facade. Photo: unidentified photographer (Helsinki City Museum)

Fig. 13: The Great Hall of the Palokunnantalo, in temporary use by the unicameral parliament (1907–10). The building was demolished in 1967. Photo: Signe Brander, 1907 (Helsinki City Museum)

During its first decade the orchestra expanded its level of activity to an average of approximately five performances a week before this figure slowly declined to about half that figure in the years up to 1913.15These figures were arrived at by sampling the numbers of performances listed in HPO data for the months January–April every five years from 1883 to 1913 (inclusive). However it became apparent as I worked on this paper and consulted online Finnish newspapers, that the dataset is incomplete so the true figures may well have been higher than my estimate. Alongside the regular popular and symphony concerts were other exceptional events – including ‘composer’ concerts: e.g. for Fredrik Pacius (1884), Svendsen (1886), Ilmari Krohn (1891, 1892, 1902), Christian Pedersen-Danning (1892), Sibelius (1892, 1893, 1895 (2), 1896, 1897, 1899 (2), 1902 (3), 1904 (3), 1907, 1911 (2)), Armas Järnefelt (1896), Erkki Melartin (1903, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1908), Sgambati (1903), Palmgren (1904, 1908), Ida Moberg (1905), Leevi Madetoja (1910) and Toivo Kuula, 1911 (2)). 16David Wright has perceptively observed that the patterns of performance suggest that Kajanus’s strategy for creating a well-trained, permanent concert orchestra parallels that adopted by August Manns at the Crystal Palace in London in the mid-nineteenth century: popular informal concerts providing regular work and income as well as ensemble-building practice that underpinned the preparation of more challenging high-art repertoire.

The first of the two performances of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 was given at the fourth of the orchestra’s 1911–12 symphony concerts at the main hall of the University of Helsinki, where seating the expanded orchestra must have been a challenge.

Fig. 15. Handbill for the first performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in Helsinki, on 20 November 1911, showing the Finnish and Swedish texts. (Helsinki City Archives)

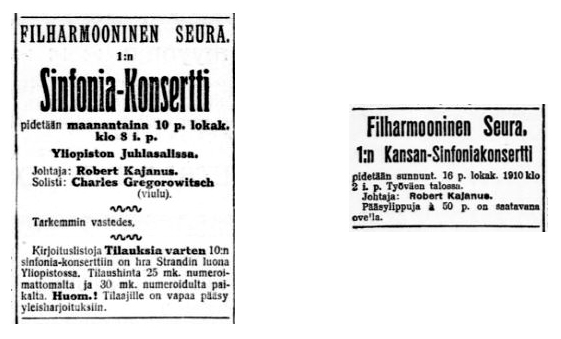

By this date the Orchestra had also evolved a newer series of concerts that in part shared repertoire with the two existing series, but seems to have had a rather different target audience. The title adopted was ‘Kansan-Konsertti’ (Peoples’ Concerts) and in the autumn of 1908 it was joined by another series, the ‘Kansan-Sinfonia-Konsertti’ (Peoples’ Symphony Concerts). A number of features clearly differentiate the two new series from the orchestra’s other concerts and suggest that they were intended to appeal to, and be accessible by, members of the working class:

- the concerts were almost always held on Sundays – the one day of the week when most workers would have free time – or on other public or religious holidays;

- the normal starting time was 14:00,17This appears to have been established as the norm in the 1902–3 season. but if held in the evening the concert would begin at 18:00 (1½-2 hours earlier than other series): these timings allowed for religious observance, and the early start of the next working day;

- the concerts were relatively short;

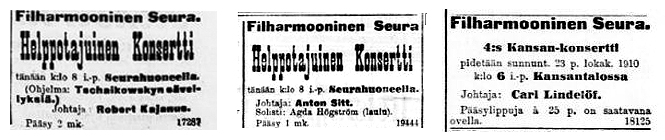

- the tickets were relatively inexpensive: entrance to the main symphony series (usually about 8 concerts) was by subscription of 25 markkas (or 30 markkas for numbered seats), but single tickets cost 4 or 5 markkas respectively;18See, for example, the advert for the second Sinfonie-Konsert of the 1910–11 season that appeared in Uusi Suometer, 23.10.1910, p. 2. a ticket to a Peoples’ Symphony Concert would cost 50 penni (i.e. half a markka) – see Fig. 14a; to attend one of the Popular Concerts would cost 2 markkas if it was conducted by Kajanus or 1 markka if conducted by someone else (usually one of the orchestra’s concert-masters, Anton Sitt or Carl Lindelöf), but attending a similar People’s Concert cost a quarter of these prices, 50 or 25 penni (see Fig. 14b).

Fig. 16a: Adverts for the opening concert of the Symphony Concert series (Helsingin Sanomat, 07.10.1910, 2) and the 1st Popular Symphony Concert (Tyomies, 15.10.1910, 2)

Fig. 16b Adverts for Popular concerts conducted by Kajanus (Uusi Suotmeter, 18.10.1910, 1) and Anton Sitt (ibid., 18.11.1910, 1) and a Peoples’ concert conducted by Carl Lindehöf (ibid., 23.10.1910, 2)

Fig. 17: Advertisement, Uusi Suometer, 29.12.1888, 1, where the opening times of the HTY offices, where tickets could be bought, are listed.

There is some additional evidence suggesting that the Peoples’ concerts were intended as social and cultural outreach. Despite the overlap in musical content, and the fact that both the Popular and People’s series tended to share venues, the title of the newer series, initiated in 1888, perhaps carries a social and political resonance absent from the former. It is also noteworthy that from the start tickets for the orchestra’s People’s concerts were to be obtained from the Helsingin Työväenyhdistys (Helsinki Workers’ Association: HTY). This implies a degree of collaboration between the orchestra and the association, but the extent and nature of the relationship between the two organisations needs to be further researched.

The initial connection with a workers’ association was perhaps less left-orientated than one might suppose. The Helsinki Workers’ Association was the first in Finland and was established in 1883 by a middle-class owner of a furniture factory, Julius von Wright (1856–1934). A social liberal, von Wright and many of his supporters were concerned to improve the conditions of the working class, by providing sports and social facilties, and cultural programmes without encouraging any demand for significant social or political change – it was only later that such associations became linked with trade unions and political parties (social democratic and communist).19The Finnish National archives have a good introduction on Worker’s Associations, but only in Finnish.

The series of Peoples’ Symphony Concerts (Kansan-Sinfonia-Konsertti) was a rather later development and the the timing of this innovation, 1908, coincides – and may therefore be linked with – another important development, the opening of the Helsinki Workers’ Association’s own building complex, the Työväentalo, on the shore of Eläintarhanlahti, and the establishment of both the Philharmonic Society’s ‘Peoples” series at the new venue.

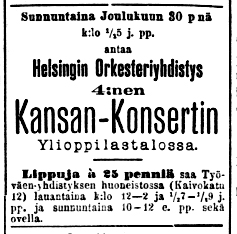

Fig. 18a: Initial work on the site for Työväentalo, 1906-07. Photo: unidentified photographer. (Paasitorni website).

The design of the building was the subject of an architectural competition won by the Swedish-born Finnish architect Karl Lindahl (1874–1930), who was chiefly responsible for the main structure, and Max Frelander (1881–1949), who was best-known for interior design: construction commenced in 1906.20For details of the competition see the listing on the The Museum of Finnish Architecture website; elsewhere on the site it is implied that the Gesellius-Lindgren-Saarinen partnership may also have been interested in this project. The preparation of the site required the removal of a granite outcrop, clearly visible in Fig. 18a, which was recycled to provide the cladding of the Finnish-Romantic exterior of Lindahl’s design.

Fig. 18b: Työväentalo viewed from Eläintarhanlahti, 1908. Photo: unidentified photographer (Paasitorni website)

If the exterior may appear somewhat austere, the interiors manage to combine functionality with understated elegance that seems to me to be both distinctively Finnish and yet also invites comparison with art nouveau, Josef Hoffmann and Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Fig. 19: Juttutupa (1909). Photo: unidentified photographer (Paasitorni website). From 1898 this was the name used by the restaurant set up by the HTY, which moved and re-opened in the Työväentalo on 19 September 1908. If the wall decoration and benches seem of their time, the more industrial feel of the metal and wood seats perhaps anticipates new trends in Scandinavian design.

Fig. 21b: Details of two plaster-work friezes, with representations of labourer’s tools, Työväentalo . Photo: Chris Banks, 2016

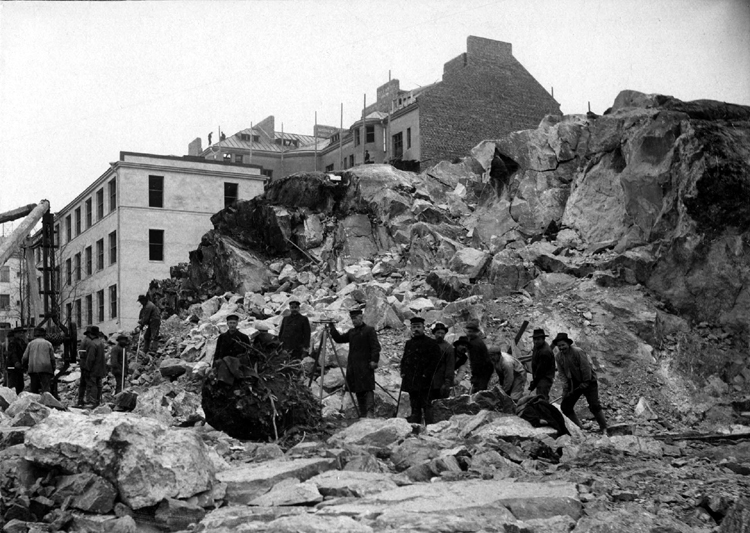

The new building was well-provided with various amenities, not least a large hall (with capacity for up to about 800 seats) for meetings, conferences and other events, including concerts.

Fig. 22a: Main Hall, Työväentalo (1909), view from the stage. Photo: unidentified photographer (Paasitorni website)

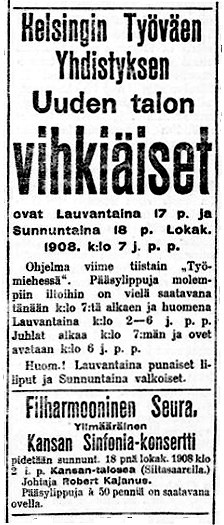

Fig. 23: Advertisements for the Inauguration of Työväentalo and the first Peoples’ Symphony Concert (Tymiöes, 16.10.1908, p. 1)

The establishment of the two ‘Peoples’ concert series at this new venue was scheduled in a way that offers further hints that there was close cooperation between the orchestra and the Workers’ Association. The first three concerts in the 1908–9 season, all Peoples’ Concerts, were given (as were all of the 1907–8 series) in the main hall of the University, for the simple reason that the Työväentalo had not been opened: the inauguration took place on the evenings of 17 and 18 October 1908, with an ‘Extra’ Peoples’ Symphony Concert on the Sunday afternoon between the two events.

The contiguous placing of the advertisements for the inaugurations and the concert in Työmies implies a planned conjunction, and both Kajanus’s involvement (most Peoples’ concerts were by this date conducted by Carl Lindehöf) and the concert’s title and programme – Beethoven’s Sixth, together with the Overture to Tannhäuser 21Both had been recently performed by the orchestra, the overture at a Popular concert on 15 October conducted by Anton Sitt and the Symphony at a Symphony Concert on 13 October under Kajanus (see HPO data). – are indications of the importance of the event, and a belief that this was best marked by a celebration of high art. Moreover, the establishment of the new series added a new strand to the cultural programme of the Association. However, the move to the new venue also coincided with a significant expansion of the orchestra’s outreach activity. Apart from the additional eight Peoples’ Symphony Concerts, the older series was expanded from seventeen concerts in 1907–08 to twenty-three in 1908–09 and these numbers of performances were maintained the following season.22Research on later years is inhibited by the fact that the digitisations of Finnish newspapers dating from after 31 December 1910 are not available online at present.

So it was in the context of this apparently flourishing concert-giving programme of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society that Mahler’s Symphony was first heard, but it appears to have made no immediate or significant impact on the orchestra’s future programming though it and a few others of his works, including the Second, Third and Fifth Symphonies and Das Lied von der Erde were heard now and then in Helsinki during the following decades, until in the 1970s Mahler established a secure place in the local repertoire.23The First Symphony was performed more frequently than most: perhaps the Orchestra had bought its own set of parts in 1911; Kajanus conducted the work on at least one later occasion, 2 March 1921 (see HPO data).

The building that has been the other focus of the narrative, Työväentalo, had a somewhat chequered history during Finland’s deeply divisive civil war in 1918.24The English-language Wikipedia article on the war is comprehensive and unusually well referenced. It became a stronghold of the Reds, a coalition led by social democrats, but as such was bombarded and severely damaged (particularly the main hall and the tower) by the Whites, the ultimately victorious coalition of conservative factions.

Happily the hall and tower were rebuilt and subsequently a new wing (also designed by Lindahl) added in 1925; then in the late 1990’s the whole complex was restored to recapture more of the original design. As the Paasitorni Conference Centre it is busy and successful (confirmed by Chris): it is not on any list of tourist sites, but it is a building of social, political, architectural and musical significance. In any case, the Juttutupa restaurant is now back in the building, and is an excellent place for good conversation and food.

This website by Paul Banks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]()

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

Footnotes

| ↑1 | This can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet or CSV file from Helsinki Region Infoshare (hereafter referred to as HPO data). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I must thank Pekka Hahle of the Helsinki City Archives for his help in locating relevant material in the archives and alerting me to other research resources, including the invaluable digitisation of Finnish newspapers (up to the end of 1910) by the National Library of Finland. |

| ↑3 | The programme was published in Hufvudstadsbladet, (05.12.1906); reviews appeared in Hufvudstadsbladet, Nya Pressen and Uusi Suometar. |

| ↑4 | See H.-L. de La Grange, Gustav Mahler, vol. 3 (Oxford: OUP, 1999), 739–767. |

| ↑5 | See the Wikipedia article, the Sarlin family webpages (Finnish and Swedish only) which include a memoir by her grandson Yrjö Raekallio, and her auotobiography, Kaiu Suomen laulu. Laulajattaren muistelmia (Helsinki 1934). I am most grateful to Erja Saraste for her help in the preparation of my article and information about the Sarlin family. |

| ↑6 | So far I have not been able to locate details of the programmes given at Kotka and Paimio. Hagelberg-Raekallio performed the Mahler song in later recitals, including one in St Petersburg in February 1909 (possibly the first public performance of a Mahler song in Russia) and those in Oulu, Raahe, Kokkola, Vaasa and Helsinki in January 1910: I am most grateful to Michael Bosworth, whose painstaking research located these later performances, for this information. |

| ↑7 | Kosti Wehanen (1887–1957) was only nineteen at the time, but was to have a distinguished career as both soloist and particularly as an accompanist; he continued to work with Hagelberg-Raekallio until at least 1911. Adverts for all these concerts may be located through the Finnish National Library website. |

| ↑8 | See Suomalainen Kansa 1906/292 (17.12.1908), 6 and Suomalainen Wirallinen Lehti 1909/9 (13.01.1909), 1. Hagelberg-Raekallio had received a similar grant for her studies in Paris, 1902–3; after her second study trip she was back in Helsinki by mid June 1909, and began advertising as a singing teacher in the autumn. |

| ↑9 | See Uusi Aura, 19.12.1911, p. 5. |

| ↑10 | Wiipuri 1908/226 (01.10.1908), 4. |

| ↑11 | See Nya Pressen, 31.10.1911, 5 and Hufudstadsbladet, 31.10.1911, 7. |

| ↑12 | The Helsinki Museum metadata describes the event depicted in Fig 11 as a Kansan-Konsertti (Peoples’ Concert). It is not quite clear what the source for this information might be, but if it is associated with the drawing, then it might be noted that this title was adopted for an important series of concerts by the orchestra that commenced in the autumn of 1888: this would explain the motivation of this sketch, which presumably represents one of the three such concerts given before the end of the year. |

| ↑13 | To English readers this may seem strange, but the service was not wholly run by municipalities and voluntary organisations maintained their own brigades. Their buildings often included large halls that could be used to generate income. I’m gratefully to Pekka Hahle for this background information. |

| ↑14 | During the next ten years the two series moved in tandem between the two venues until 1904 when the People’s concerts moved first to Palokunnantalo and then, in 1907, to the main hall of the University (the Popular concerts remained meanwhile at Seurahone). The motivations for these moves are not immediately apparent. |

| ↑15 | These figures were arrived at by sampling the numbers of performances listed in HPO data for the months January–April every five years from 1883 to 1913 (inclusive). However it became apparent as I worked on this paper and consulted online Finnish newspapers, that the dataset is incomplete so the true figures may well have been higher than my estimate. |

| ↑16 | David Wright has perceptively observed that the patterns of performance suggest that Kajanus’s strategy for creating a well-trained, permanent concert orchestra parallels that adopted by August Manns at the Crystal Palace in London in the mid-nineteenth century: popular informal concerts providing regular work and income as well as ensemble-building practice that underpinned the preparation of more challenging high-art repertoire. |

| ↑17 | This appears to have been established as the norm in the 1902–3 season. |

| ↑18 | See, for example, the advert for the second Sinfonie-Konsert of the 1910–11 season that appeared in Uusi Suometer, 23.10.1910, p. 2. |

| ↑19 | The Finnish National archives have a good introduction on Worker’s Associations, but only in Finnish. |

| ↑20 | For details of the competition see the listing on the The Museum of Finnish Architecture website; elsewhere on the site it is implied that the Gesellius-Lindgren-Saarinen partnership may also have been interested in this project. |

| ↑21 | Both had been recently performed by the orchestra, the overture at a Popular concert on 15 October conducted by Anton Sitt and the Symphony at a Symphony Concert on 13 October under Kajanus (see HPO data). |

| ↑22 | Research on later years is inhibited by the fact that the digitisations of Finnish newspapers dating from after 31 December 1910 are not available online at present. |

| ↑23 | The First Symphony was performed more frequently than most: perhaps the Orchestra had bought its own set of parts in 1911; Kajanus conducted the work on at least one later occasion, 2 March 1921 (see HPO data). |

| ↑24 | The English-language Wikipedia article on the war is comprehensive and unusually well referenced. |