[This is a lightly revised text of the 2008 Crees Lecture (which also formed my inaugural lecture as Professor of Historical Musicology) given at the Royal College of Music on 10 March 2008.]

A conservatoire such as this is a melting pot, bringing together not only staff and students from around the world, but also providing an environment where a number of different professional groups co-exist, interact and collaborate. In particular, curators, scholars and musicians mingle at the Royal College of Music. Of course, most of the library staff, curators and scholars here have received at least some training as musicians, but in addition they have acquired the often complex network of professional skills and priorities associated with their specialisms. This evening I am going to explore some of the points of contact between these specialisms where misunderstanding can arise, differing priorities rub shoulders; I’m also going to celebrate some instances where the interactions have been, or can be wholly constructive.

In seeking the fault lines between these communities the easy option would have been to home in on the metalanguages that curators and scholars have evolved. There are times when it feels as though we are indeed three professions divided by three languages. Most performers or scholars listening-in on an in-depth discussion of spatial terms and other cataloguing issues encountered during the recently completed Concert Programmes Project would have needed surtitles; I’m still only at the ‘naming of parts’ stage in the field of organology and it would not be difficult to select a page from Alan Forte’s The Structure of Atonal Music to baffle many performers and curators. At what point did this babel of voices begin to emerge? In the mid-eighteenth century the three professions had hardly separated: individuals might be involved in curatorship or scholarship – might even focus on these areas of activity – but within the overall profession of a musician.

Fig 1. William Boyce, attributed to Mason Chamberlain (c.1765-70).

Oil on canvas, 75 x 62cm

Royal College of Music.

That is how it was for William Boyce. Spurred on by the earlier plans of his mentor, Maurice Greene, and the cathedral organist at Litchfield, John Alcock, Boyce assumed the task of preparing a practical edition of the Anglican choral repertoire stretching from Tye to Croft. Over the years printed and manuscript sources for this repertoire had acquired a patina of non-authentic readings. Boyce’s aim was to preserve the music of past masters ‘in its original purity’. The result was his Cathedral Music, issued on subscription between 1760 and 1773, which established a canon, and remained in use for over a century. This has been described, anachronistically, as ‘a landmark in the history of musicology’: Boyce would have thought of himself as a musician, and the terms Musikwissenschaft or Musikforschung were not widely used before the middle of the nineteenth century, and ‘musicology’ perhaps not much before 1915. As it happens, Boyce’s initial printing was not a huge success; as we shall see, performers do not always greet with enthusiasm the pearls cast before them.

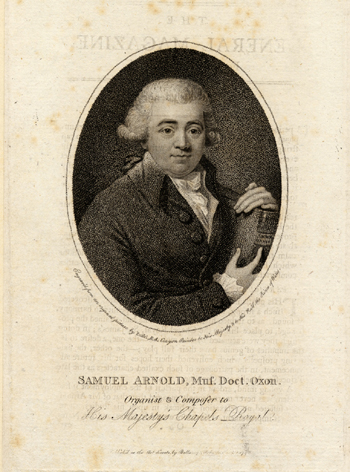

Fig. 2: Samuel Arnold. Stipple engraving, from an original painting by ?Russel, R.A. (London: Bellamy, 1798) (Royal College of Music)

Undaunted, Boyce’s colleague, the composer Samuel Arnold (1740-1802) published a continuation in 1790, but by then he had also begun another series of even greater importance, his projected complete edition of the works of Handel (1787-97). Finding ‘definitive’ versions of the works proved problematic, but Arnold made a serious effort to do so and in some cases had access to manuscript sources now lost. Unfortunately Arnold suffering the terminal effects of scholarship – he died from injuries sustained when he fell from library steps – and his project remained incomplete and without a direct successor in Britain until 1843. Moreover, one biographical detail in this sad story points to an issue of wider historical importance: that the library steps were Arnold’s own, as was the library. Until the second half of the nineteenth century there were relatively few substantial collections of music and books on music freely accessible to the public, so music scholars often had to rely on their own collections, or private libraries to which they were given personal access. Even national collections, like that of the British Museum, had restricted access – indeed the minimum age for a readers pass was raised in 1862 from 18 to 21 because the reading room was frequented by ‘too many youths for whom it was never intended.’ And it was only much more recently that it ceased to consider itself to be a collection of last resort. However, as far as music was concerned, access to the Museum’s collection was even more problematic because the first set of cataloguing rules was not formulated until December 1840, when Anthony Panizzi, the Keeper of Printed Books, submitted a report recommending how it should be accomplished. As music librarians are now tired of having to explain, providing readers of music with a usable catalogue that will enable them to search efficiently is much more difficult than providing the same service to readers of books. A single musical work can be published in a variety of formats – scores, parts – or arrangements (by other musicians) for a variety of instruments, it may use texts (another author to be indexed), and the titles under which it is published may be varied and numerous. The evidence is that Panizzi was unmusical, so it is remarkable that he came up with rules that in part underpin contemporary practice. Work on the catalogue started in 1841.

Arnold’s ambitious Handel edition remained unfinished, and it was in Germany that the strategy of publishing complete scholarly editions of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century composers who formed the core of the emerging canon, was taken up by various individuals, editorial committees and one publisher: Breitkopf und Härtel. The first such project, the Bach Gesellschaft Edition (1850–99) spanned virtually the whole of the first phase of the endeavour during which research techniques were enhanced, textual analysis became more sophisticated, and a distinct scholarly discipline of musicology emerged, fostered by, among others, the Bohemian, Guido Adler (of whom, more later). Since then editorial techniques have continued to evolve further, and this process ensures the eventual obsolescence of earlier editions. We now have the New Bach Edition, the New Mozart Edition, the New Berlioz Edition. Which composer will be the first to have the accolade of a New New Edition I wonder. The evolution of principles can be illustrated very simply: if you wish to play from a copy of Mozart’s piano sonatas that accurately preserves his meticulous notation of stem directions (which provides strong evidence of his conception of voice leading, of some importance to a performer), you would not turn to either the Wiener Urtext Edition, or the New Mozart Edition – both highly respected late twentieth-century scholarly editions that silently modernise Mozart’s notation – but to a newer, practical teaching edition (complete with fingering and other discrete editorial suggestions) by the late Stanley Sadie, and published by the Associated Board in 1980.

Satisfying the desire to provide the performer with a text that accurately reflects the intentions of the composer in a practical format while also offering the scholar a volume that will document the editorial process can be challenging. Some works provide particularly intractable problems. A good case in point is the first of Berlioz’s operas to be performed, Benvenuto Cellini. He subjected the piece to much revision, but three relatively well-defined versions can be identified: the score as initially copied for the Paris Opera in early 1838; the text of the archive score prepared after the initial run ended in 1839, and the version published in 1856 after performances in Weimar and London. Normal editorial practice would have been to choose a copy text and consign all the variants to be found in the other versions to the dark recesses of an appendix. However the editor, Hugh Macdonald, came to the conclusion that this arrangement would make it very difficult for a conductor to use the score for a performance of any version other than the one he, as editor, had chosen as his main text. So he decided to prepare a score that incorporated all the variant versions in a single continuous sequence, but with a specially developed, and elegantly simple, system of signage. At any point in the score the conductor knows what version he is in, and when he comes to the end of the section, he is told to which page he needs to turn for the continuation of the score in that version. All he needs to do beforehand is sit down with the score and a box of paper clips (plastic not metal, I trust) and clip together the pages he doesn’t need for the version he has chosen. One might think that such an elegant solution would win plaudits from the conducting profession. Alas, no. The publishers, Bärenreiter Verlag, report that many conductors can’t be doing with this, and just want a score containing only the text of the version they have selected.

In some cases performers have expressed more fundamental reservations about the activities of scholarly editors: whether some works they laboured over should have been published at all. After Brahms’s death in 1897, Guido Adler needed a replacement on the Board of the Monuments of Austrian Music, a series of scholarly editions of which he was general editor. Adler turned to his friend, Gustav Mahler, recently appointed Director of the Court Opera in Vienna, who soon found the editorial meetings intensely tedious and some of the music quite unworthy of publication. For rather different reasons – ethical rather than aesthetic – the performance and publication of Mahler’s own unfinished Tenth Symphony in Deryck Cook’s Performing Version ran into strong opposition from performers (and some scholars) who felt that it was not appropriate to tamper with the composer’s sketches in this way. This version – not a completion, as Cooke was always at pains to point out – is an astonishing achievement, combining scholarship and creativity in a way that I believe would have been impossible for someone nurtured in the German-American school of musicology. For Cooke was English, and of a generation educated before ‘Musicology’ with a capital M had taken root in the UK: untouched by the positivism that Joseph Kerman so famously railed against because of its influence on American scholarship, Cooke was in a position to be methodologically scrupulous, but also to intervene, as discretely as possible, to render Mahler’s continuous sketch playable. Thanks to him, and his collaborators, Berthold Goldschmidt and Colin and David Matthews, we can hear music that would otherwise have remained mute for rather longer, and in the printed score we can see the nature of the interventions, because a transcription of the sketch is printed below the performing version.

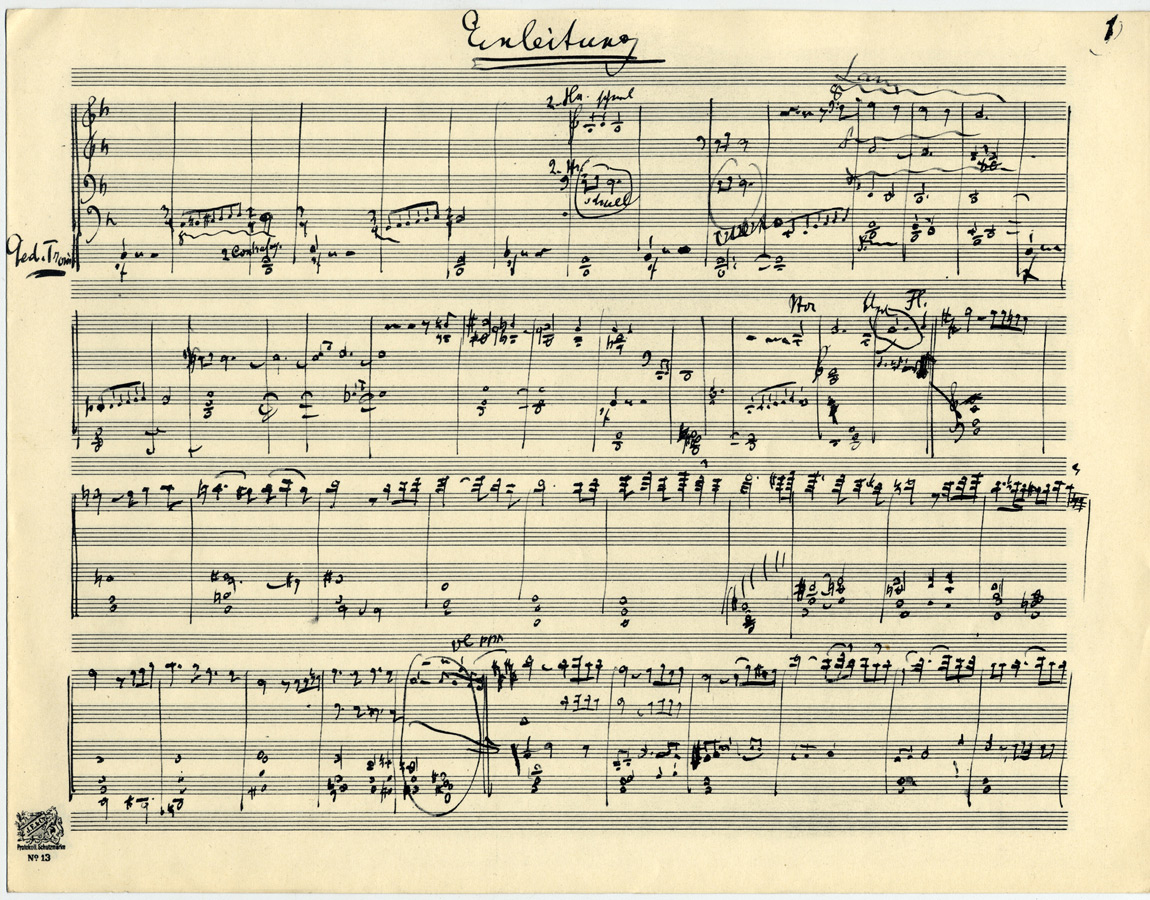

Fig. 3a: The opening (bb. 1–50) of the short score of the fifth movement of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony (1910). (Berlin-Vienna-Leipzig, Paul Zsolnay Verlag, 1924). [Click on the image for a larger version]

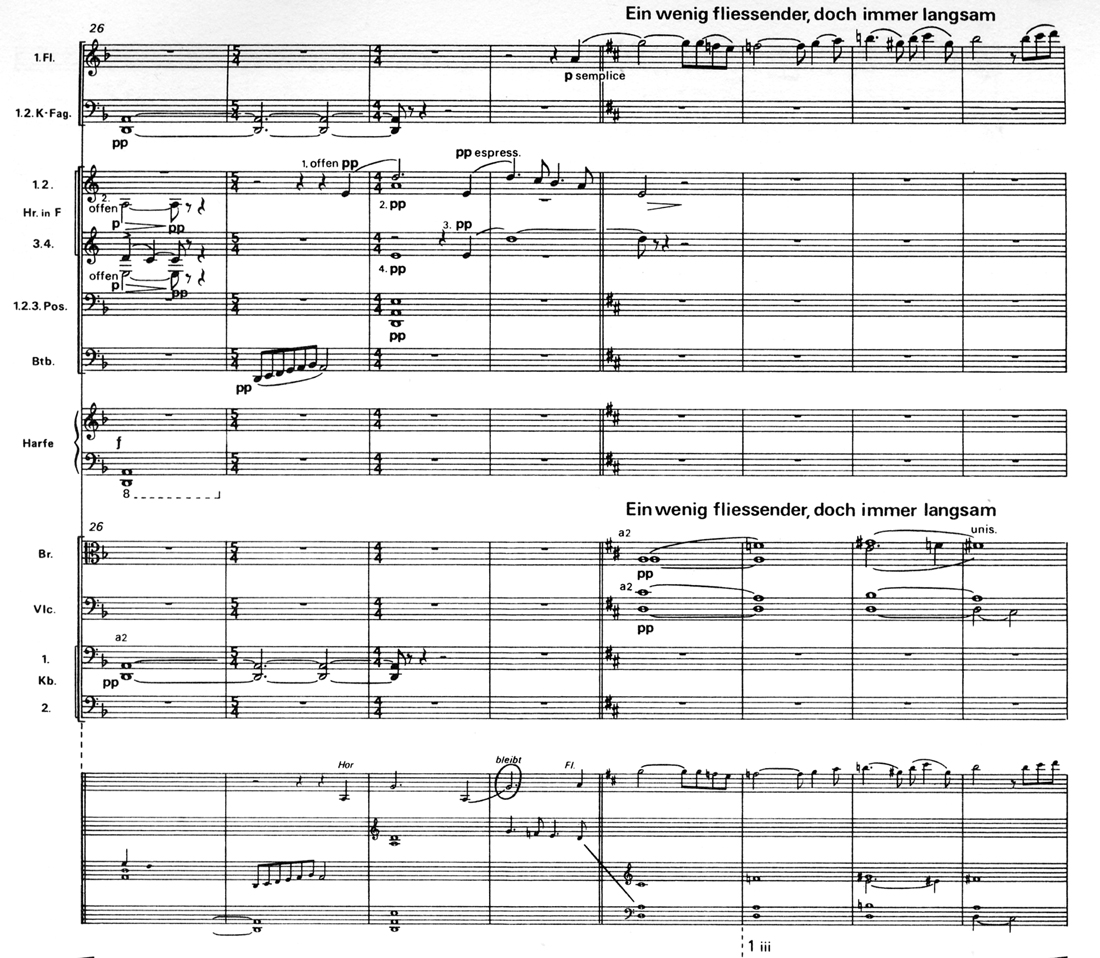

Fig. 3b: Mahler: Tenth Symphony, fifth movement, bb. 26–33, in the performing version by Deryck Cooke, et al. (New York/London: AMP/Faber Music, 1976). [Click on the image for a larger version] The passage can be heard online (from 51:30 onwards)

If historical musicology has evolved over the last 150 years, there has been a parallel development in the priorities of curators (using that term as widely as possible) and a recognition that their decisions about all aspects of collection management need to be informed by criteria that are not merely based on their own values, convenience and immediate needs, but on the interests of all the possible communities of users, including those not yet born. The practice of curators tends to develop in response to the changing types of question asked by users, and to the new techniques available to answer those questions.

In the past many curators of instrument collections had no hesitation in restoring instruments that could be rendered playable, and there seems some common sense behind this approach: why keep an instrument if you can’t hear what it sounds like? The problem is that when we listen to the magnificent Kirkman harpsichord in the RCM Museum we are listening to an instrument that has long outlived its maker’s most optimistic expectation of its working life. Many of the original components will have been replaced, and those that remain will have aged during the last 250 years. So we delude ourselves if we assume that what we hear now – wonderful though that is – is exactly how it would have sounded in its prime. Equally, playing on it may in some respects inform the performer about how it might have felt to play the instrument in the 18th century, but in both respects – aural and tactile – the experience needs to be interpreted with great care.

Here we have a major fault line between two of our communities, one that is made more acute by the fact that some organologists now wish to gain a more detailed understanding of the original materials and manufacturing techniques used by instrument makers so that they may be employed as nearly as possible in the creation of modern copies. Any restoration work will almost inevitably destroy some of the evidence they seek. As an alternative the results of new, non-invasive techniques for examining old instruments, developed in collaboration with various scientific disciplines, when applied to the creation of modern copies can yield very impressive results as we know from the outstanding work of the Göteborg Organ Art Centre. Copies, and the research needed to better inform their creation, are expensive, but this, surely is the way forward to provide performers with new, relatively robust copies on which to explore earlier repertoires.

Not so long ago libraries, too, adopted radically interventionist strategies: when binding manuscripts some libraries separated the two leaves that made up bifolia, and pasted the resulting single leaves onto stubs; even worse, some binders simply discarded any leaves that had no writing on them. In both cases, as a result these interventions it is now often difficult to reconstruct the original physical structure of such manuscripts, information that can sometimes shed light on the composer’s working methods. Printed editions often suffered a similar fate: any paper covers or wrappers would simply be discarded during the binding process, thereby removing evidence of the work’s marketing, the history of other works (included on adverts), provenance, and the date of the particular copy concerned.

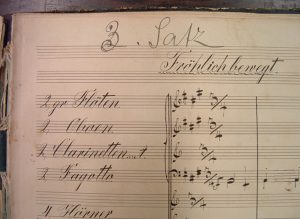

I’ll give one example of the benefits to be gained by leaving well alone – it concerns an important source of Mahler’s First Symphony. Mahler’s nephew, Wolfgang Rosé inherited a substantial collection of memorabilia from his parents, the concertmeister of the Vienna Philharmonic and the Court Opera, Arnold Rosé, and Mahler’s sister, Justine. Wolfgang was himself a musician and emigrated to North America, ending his career on the faculty of the University of Western Ontario. Rosé and his widow bequeathed his collection to the University library where it has been housed in the Mahler-Rosé Room for some years. The collection is large, and contains a number of manuscripts, including one originally listed as an incomplete arrangement by Bruno Walter of three movements from the First Symphony. As such it attracted no attention until Stephen McClatchie was examining the whole collection in the mid 1990s. He recognised it for what it is: the earliest surviving source of the symphony, a manuscript copy (probably prepared in 1888-9) with numerous autograph annotations and revisions made by Mahler, mostly as he prepared for a thorough overhaul of the Symphony in 1893. This discovery was particularly exciting because no sketches, drafts or autograph fair copy of the first version, finished in the late spring of 1888, survive. The manuscript offers many insights into Mahler’s first thoughts on the scoring – it’s for an entirely conventional, Brahms-sized orchestra – and structure – the finale had a quite different formal design at this stage.

But in one respect the Rosé manuscript seemed to muddy waters that had been relatively clear. The programme of the first performance – in Budapest in 1889 – and later printed programmes and manuscripts all indicated that up to 1896 the work included a short movement – now commonly called Blumine – placed immediately after the opening movement and before the scherzo. Blumine and the slow movement – the latter is placed in all known sources immediately before the finale – are, unfortunately not present in the Rosé manuscript, and, even more confusing is the fact that Mahler himself re-numbered the scherzo:1All of the photographs reproduced here were taken and supplied by Lisa Philpott (University of Western Ontario Library) to whom I am most grateful.

Fig. 4: Fol. 39r of the first copyist’s manuscript of Mahler’s First Symphony. CDN-Lu Mahler-Rosé Collection OS-MD-694 [Click on the image for a larger version]

It may well be that Stephen McClatchie’s opinion,2Stephen McClatchie, ‘The 1889 version of Mahler’s First Symphony: a New Manuscript Source’, Nineteenth-Century Music XX/2 (Fall, 1996), 99–124 that the ‘2’ was merely an error on Mahler’s part, is correct, but it leaves unanswered the more fundamental questions about why Mahler was making an annotation at all, why there was a possibility of confusion in his mind and indeed how many movements there were in the Symphony before he made the annotation? Fortunately the current physical structure of the document – which has been spared the interference of the conservation department – provides some clues, which, while necessarily only indicative, provide evidence that underpins the conjectures that follow.

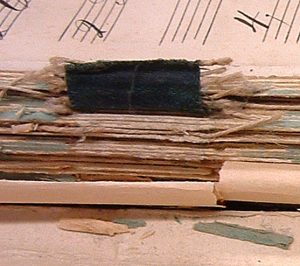

The manuscript is currently bound in two volumes in boards covered in black cloth; the mainly stacked bifolios are glued into gatherings and stitched onto tapes (two per volume) originally attached to the boards. The first volume now contains the first movement and scherzo, so, bearing in mind the movement order at the first performance in Budapest, with Blumine placed second in the sequence, the questions that come to mind are: at the time of binding did this volume contain one or more of the now-absent movements (and more especially Blumine), and if so, where were they situated? Sadly the pagination of the volumes (which have separate sequences for each of the movements) offers no clue. However, the binding of the first volume is very loose, making examination of the tapes and threads used in the binding process relatively straightforward.

Fig. 5a: Detail of the binding of the ms., showing the lower binding tape and sewing threads (Vol. 1, fol. 38v–39r) [Click on the image for a larger version]

Fig. 5b: Detail of the ms., Vol. 1, fol. 38v–39r, showing the upper binding tape and sewing threads. [Click on the image for a larger version]

As there is no evidence of any remnants of threads that might have supported sheets that have been subsequently removed it seems unlikely that this volume ever contained either of the missing movements.

The second volume is in a rather more distressed condition, which fortunately facilitates examination. Here the tapes have become detached from the front covers, and it is easy to observe that they still have attached to them the remnants of three severed threads that must have originally supported gatherings that were subsequently removed:

Fig. 6a: Detail of the ms., Vol. 2, fol. 1r, showing the binding tapes and sewing threads. [Click on the image for a larger version]

Fig. 6b: Detail of the ms., vol. 2, fol. 1r, showing the upper binding tape and sewing threads. [Click on the image for a larger version]

Fig. 6c: Detail of the ms., vol. 2, fol. 1r, showing the lower binding tape and sewing threads. [Click on the image for a larger version]

How many movements, then, have been removed? By examining the structure of this manuscript it is possible to arrive at an informed estimate of the number of bifolios that could have been present. The binder seems normally to have glued three (sometimes four) bifolios together at the fold edge and stitched through the fold of the first to secure the glued gathering to the tape. So between nine and twelve bifolios were probably present at the start of the volume when it was bound. Turning to the next two manuscript sources for the work, an autograph score and a second manuscript copy, it is apparent that the first movement and scherzo occupy very nearly the same number of manuscript pages in all three documents. Turning to the two movements missing from the Rosé copy, we find that they occupied in total 10 and 9 bifolios respectively in the two later manuscripts. This strongly suggests that both movements were originally bound at the start of the second volume, though in what order cannot now be determined on the basis of the binding evidence. Nevertheless it is striking that at the first three performances the work was described as being in two parts, with the slow movement and finale forming the second part. This division, which reinforces the fundamental contrast between the relatively uncomplicated and optimistic emotional world of the first three movements and the complex and troubled music of the last two movements seems central to the narrative of the work. So unless Mahler fundamentally rethought the contours of the work after the Rosé score was bound – not entirely impossible, as he rethought the Sixth Symphony at an even later stage in the work’s evolution – the balance of probabilities is that when the manuscript was bound Blumine was placed third in the sequence. The renumbering of the Scherzo was to reverse the order of the second and third movements, presumably before the first performance. This supposition gains support from a detail in the programme for the work recorded by Mahler’s confidante Natalie Bauer-Lechner in 1900 following their conversations about the work; after discussing the scherzo she notes:

Following this, there was originally a sentimentally indulgent movement, the love episode – which Mahler jokingly called the ‘youthful folly’ of his hero. Later, he removed it.3 Herbert Killian, Gustav Mahler in den Erinnerungen von Natalie Bauer-Lechner, revidierte und erweiterte Ausgabe (Hamburg: Karl Dieter Wagner, 1984), p. 173

Far from being an error or misunderstanding (which it might otherwise appear) it now seems that Mahler may have been correctly reporting the original movement order of the Symphony, with Blumine placed third.

Here benign neglect is to be applauded. I hope my colleagues in Ontario don’t rush to rebind these volumes, as they will almost certainly contain other clues that I have overlooked. However this story should also serve to emphasise the importance of thorough, informed cataloguing: if an item is not catalogued it may be almost invisible to both its custodians and the users of the library. There are some advantages to such invisibility, not least in minimising damage through over use, or complete destruction. Before the 1990s music librarians in the Czech lands feared that some materials in their collections might be in danger of being ‘purged’: their solution was to remove all the cards relating to these items from the catalogue, and take them home, to be hidden beneath their mattresses, awaiting the time when they could be returned to their catalogue trays. Hearing this story was one of the most moving learning experiences for delegates at the meeting of the International Association of Music Libraries and Information Centres held in Prague in 1991. The majority of the delegates had never had to consider the desirability of sabotaging a catalogue. Indeed, the Association’s whole ethos tends in the opposite direction.

Since its founding in 1951, IAML has formed what we would now call strategic alliances with other professional groups, notably the International Musicological Society, to establish the so-called ‘R’ projects – RISM, RILM, RIdIM, RIPIM – all of which are concerned with the enhancement of access across the world to early printed and manuscript music, new publications about music, images of music and historical publications about music. In recent years two new projects with strong IAML connections, smaller in scale, but nevertheless path-breaking, have come to completion.

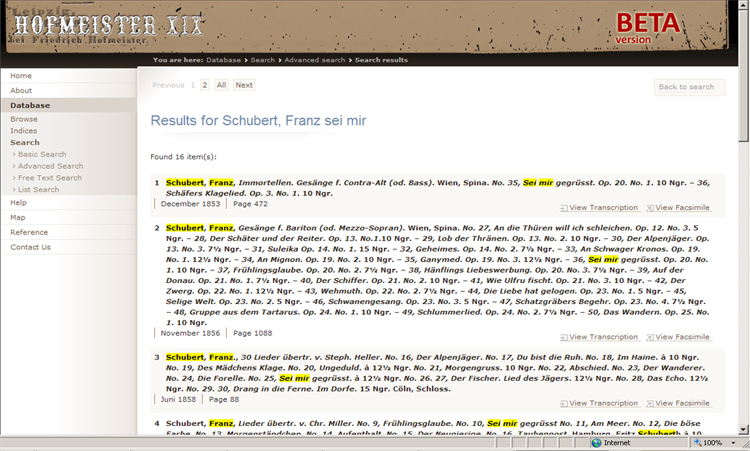

Many years ago the late Neil Ratliff drew IAML’s attention the usefulness of Hofmeister’s Monatsbericht, a monthly trade compendium that from 1829 listed new music publications. The coverage centred on the German states, but by the mid century the German music publishing business was dominant, and in any case there was a significant coverage of other European countries. In effect it was a Germany-centred bibliography of music (it continues today as the Deutsche Musikbibliographie) and potentially offered access to information about a vast repertoire of printed music.

The problems were that no complete set of the volumes covering the nineteenth century existed in any one library, that these volumes were estimated to contain millions of entries, and they were un-indexed. For this reason only the most dedicated scholars had previously used the Monatsbericht. Computer technology seemed to offer the possibility of providing an indexed version and ten years of preparatory work in the IAML Working Party on Hofmeister XIX formed the basis for a successful AHRB bid under the much lamented Resource Enhancement Scheme. The Project, which provides a searchable interface has been completed, and is automatically linked to the results of a parallel project, hosted by the Austrian National Library that provides scanned images of the volumes.

Fig. 7: screenshot of the first four search results for ‘Schubert Franz, sei mir’ in Hofmeister XIX.

The opportunities this resource offers performers searching for information about obscure works, and scholars interested in issues such as the history of the music publishing business, the development of the canon, and the reception history of music are enormous. This is an example of curators providing scholars with a resource that not many knew they needed.

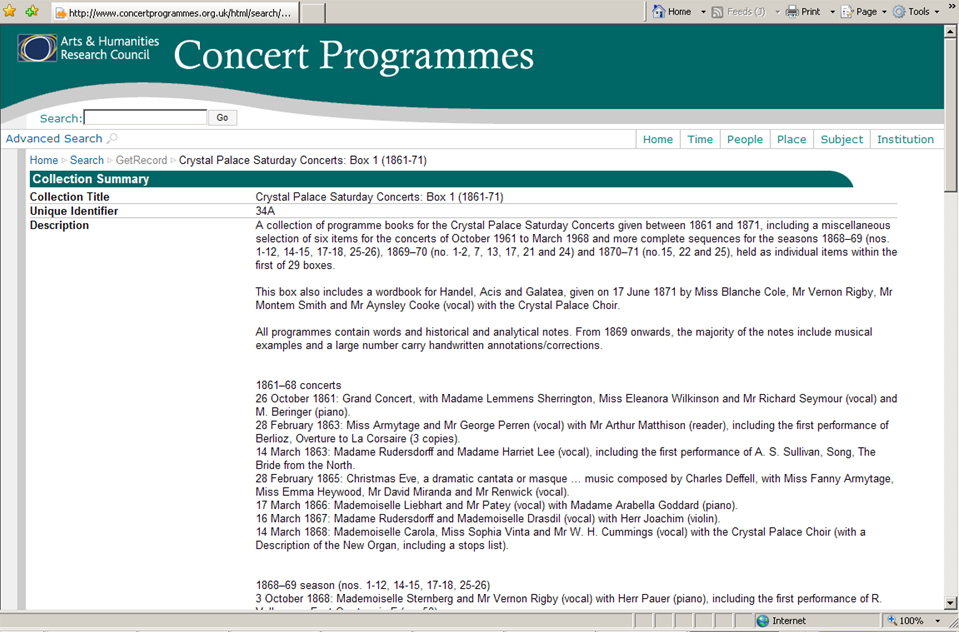

On the other hand, the second project stemmed directly from a suggestion from a scholar – Lewis Foreman – and responds to the increasingly fruitful research being undertaken in the area of performance history, the study of social and economic history concert life. The development of such research has been hindered by the fact that it has been very difficult to track down one of the chief documents sources of information – concert programmes. These are often almost invisible to researchers because librarians have never come up with an agreed cataloguing standard for these documents. Because of the resulting uncertainty, programmes in public collections have often been either given very brief entries, that failed to adequately describe what was present, or no entry at all; this of course made the programmes themselves vulnerable to culling: since they were not being used, why keep them?

To gain a more comprehensive picture of the situation in the UK and Ireland, the Music Libraries Trust funded a scoping study by Dr Rupert Ridgewell: this made it clear that some database describing the publically accessible holdings of concert programmes in the two countries was highly desirable. A team led by Professor John Tyrrell, with the RCM as partner, and Rupert Ridgewell as Project Manager, put together a successful bid for AHRB Resource Enhancement funds and the first phase of the project came to a successful conclusion last October:

Fig. 8: screen-shot of the entry in the Concert Programmes database for the collection of Crystal Palace concert programmes held by the Royal College. of Music.

Here we have a description of one box of the RCM’s holdings of programmes of concerts given at the Crystal Palace.4This interface has since been replaced by an entirely new and more flexible design. So now researchers know where they may find a copy of the programme for a specific event. But the records in the CPP database don’t by default give details of what was played and by whom. How we might supplement the original database, to provide answers to those and other more specific questions is now under discussion.

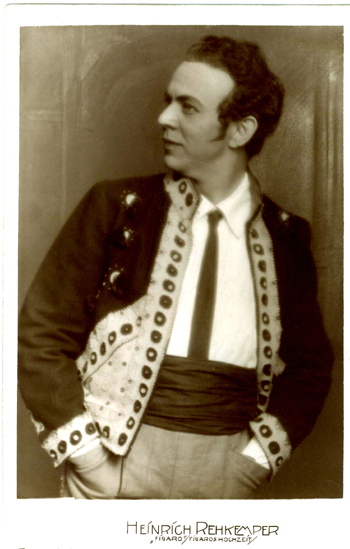

So far I’ve explored briefly how curators and scholars interact with one another and with performers, but what about the performer’s contribution. One important element is the performer’s ability to reveal previously unsuspected insights into a work, to set scholars thinking yet again about a familiar piece and trying to understand what a performance is communicating. This happened to me a few years ago when I made a speculative purchase of a CD while on a trip to Vienna. I noticed this recording largely because the singer, the German baritone, Heinrich Rehkemper, made the first (and in my view, one of the very finest) recordings of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, in 1928.

So when I found a CD transfer of his recordings of Schubert I couldn’t resist exploring. The very first item was a performance of Sei mir gegrüsst, D. 741, a setting of a poem by Friedrich Rückert, who was coincidentally the poet of Kindertotenlieder. This was also recorded in 1928, and the very sympathetic pianist was the composer Manfred Gurlitt, famous mostly for making the dreadful mistake of setting Büchner’s Wozzeck at almost exactly the same time as Alban Berg. After a few bars I was captivated: here was the warm voice, the elegance and sense of engagement that was instantly recognisable:

Mus. ex. 1: Schubert, Sei mir gegrüsst, D741, bb. 1–29.

Herman Rehkemper (baritone), Manfred Gurlitt (piano), rec. 1928.

In some ways we know very little about the composition of the song.5For a .pdf of the song. edited by Eusebius Mandyczewski, click here. The manuscript is lost, but it was probably written in 1822, shortly after the publication of the poem, and was published with Schubert’s other Rückert settings the following year. But we have one anecdote concerning an early performance of the song, retold by the singer involved, Ludwig Josef Cramolini (1805–1884):

It was in the early twenties that Capus von Pichelstein came to me one morning, and brought me Schubert’s divine song, “Sei mir gegrüsst”, from Rückert’s ” Oestliche Rosen”, and asked me to sing it a few days later at a Serenade, which he wanted to present for his fiancée, Fräulein von Berthold, on her birthday; he himself wished to accompany me on the harp, which he played excellently. I expressed my readiness and we studied the song, under Franz Schubert’s guidance, in my apartment.

Capus, at that time, had fallen out with his fiancée and hoped, by this means, to become reconciled to her again, and in this he was completely successful. On the evening in question we drove – Schubert, the admirable ‘cellist Merk, the violinist Schuppanzigh, Capus and my humble self – to the hamlet of Kahlenberg, where the Berthold family had a property ; we waited until the lights in the house were extinguished and then began the Serenade with a Trio for violin, ‘cello and pedal harp.

After this I sang Schubert’s “Ständchen” with harp accompaniment, then followed a Fantasy by Thalberg, played by Capus, then I sang Schubert’s song, “Sei mir gegrüsst”, and in such a way that Schubert embraced me and said ” No one can sing that song as you do; you have drawn tears from us all “, a commendation which gave me immense pleasure and caused me to sing the same song again often and always with similar success.6Schubert: Memoirs by his Friends, collected and ed., O.E. Deutsch (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1958), 262.

So, if not composed as a serenade, it was a song that Schubert and his friends thought – rightly – would serve well in that role. Indeed, this anecdote sheds light on Schubert’s instruction that the pianist should play with the dampers raised, presumably to create a harp-like sound. This doesn’t make a very agreeable effect on modern instruments and today most pianists ignore the instruction, but played on the 1821 Viennese action grand by Bertsche in the RCM Museum, the effect works well.

Rehkemper’s suave performance of the first stanza might suggest that he, like many other performers of the song, and some commentators, accepted Pichelstein’s view of the piece, as a serenade. However, what follows in his recording reveals that he had discerned a rather different way of approaching it, one that suggests that, like Mahler after him, Schubert had discovered in Rückert’s potentially sentimental words, a rather more disturbing subtext.

Rückert was a scholar of oriental languages who held various professorial appointments before – as one biographical note wryly puts it – retiring to devote himself to scholarship. So it is not a surprise that this poem is often described as a Gahzel, based on Persian models. It is cast in five quatrains, all of which end with the same line; the first stanza, though is anomalous, in that the refrain also appears as the second line:

O du Entrissne mir und meinem Kusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!

Erreichbar nur meinem Sehnsuchtsgruße,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!Du von der Hand der Liebe diesem Herzen

Gegeb’ne. Du, von dieser Brust

Genommne mir! Mit diesem Tränengusse

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!Zum Trotz der Ferne, die sich feindlich trennend

Hat zwischen mich und dich gestellt;

Dem Neid der Schicksalsmächte zum Verdrusse

sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!Wie du mir je im schönsten Lenz

Der Liebe mit Gruß und Kuß entgegenkamst,

Mit meiner Seele glühendstem Ergusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!Ein Hauch der Liebe tilget Raum und Zeiten,

Ich bin bei dir, du bist bei mir,

Ich halte dich in dieses Arms Umschlusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt!

However, Schubert makes some changes:

O du Entriss’ne mir und meinem Kusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!

Erreichbar nur meinem Sehnsuchtsgruße,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!Du von der Hand der Liebe diesem Herzen gegebne!

Du, von dieser Brust genommne mir!

Mit diesem Tränengusse

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!

Zum Trotz der Ferne, die sich feindlich trennend

hat zwischen mich und dich gestellt;

Dem Neid der Schicksalsmächte zum Verdrusse

sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!Wie du mir je im schönsten Lenz der Liebe

Mit Gruß und Kuß entgegenkamst,

mit meiner Seele glühendstem Ergusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!

Ein Hauch der Liebe tilget Raum und Zeiten,

Ich bin bei dir, du bist bei mir,

ich halte dich in dieses Arms Umschlusse,

Sei mir gegrüßt, sei mir geküßt, sei mir geküßt!

Throughout he adds an extra repetition of the phrase ‘Sei mir geküsst’ in the refrain; the effect is to undermine the apparently unambiguous meaning, just as Schumann’s repetitions of ‘Ich grolle nicht’ in the song from Dichterliebe (along with other features of the setting) imply that the singer means the opposite of what he is singing.

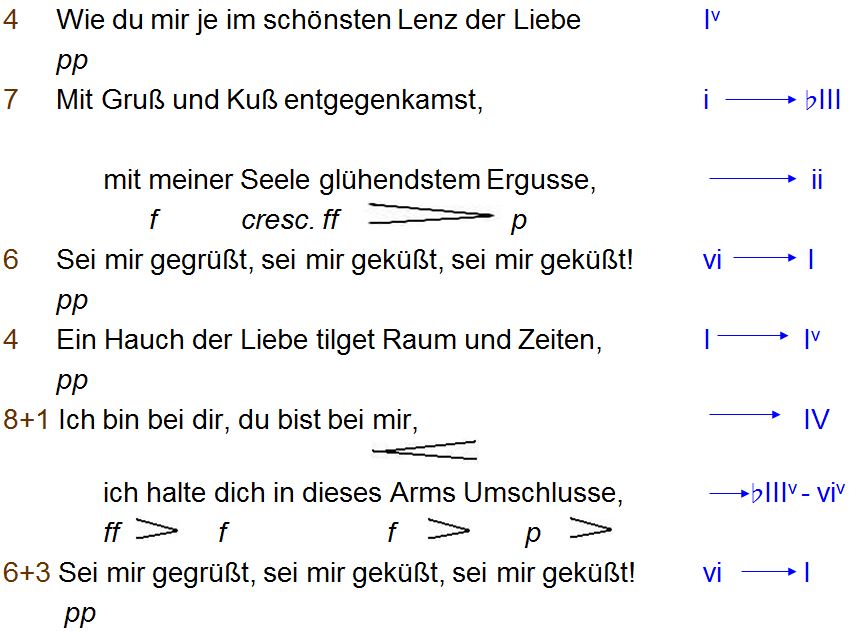

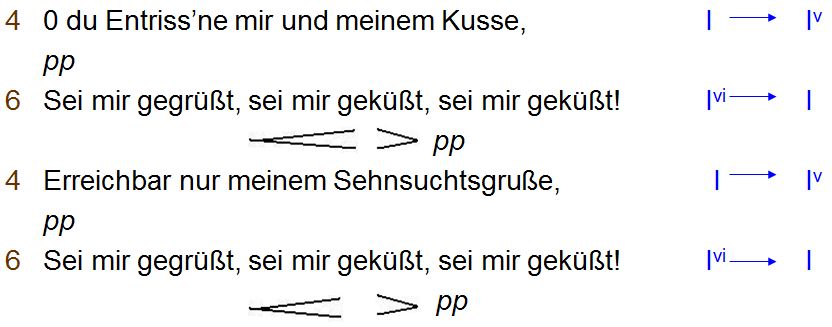

In Schubert’s song the additional phrase has another effect, though: it forces the composer to modify the regular four-bar phrasing that is established by the piano introduction and the first line. It turns out that this is perhaps a subtle suggestion that the words and music are in danger of breaking out of the confines of a simple serenade:

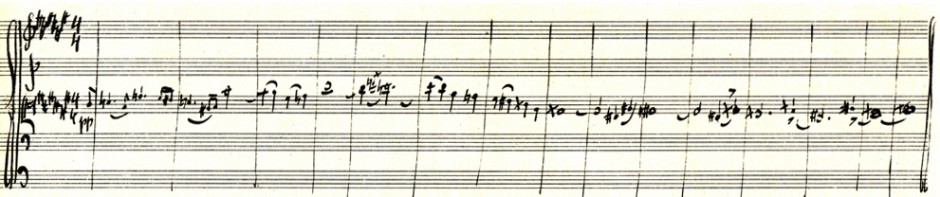

Fig. 10: Schubert: Sei mir gegrüsst, D741. Outline of the phrase lengths, tonal structure and dynamics in the first stanza.

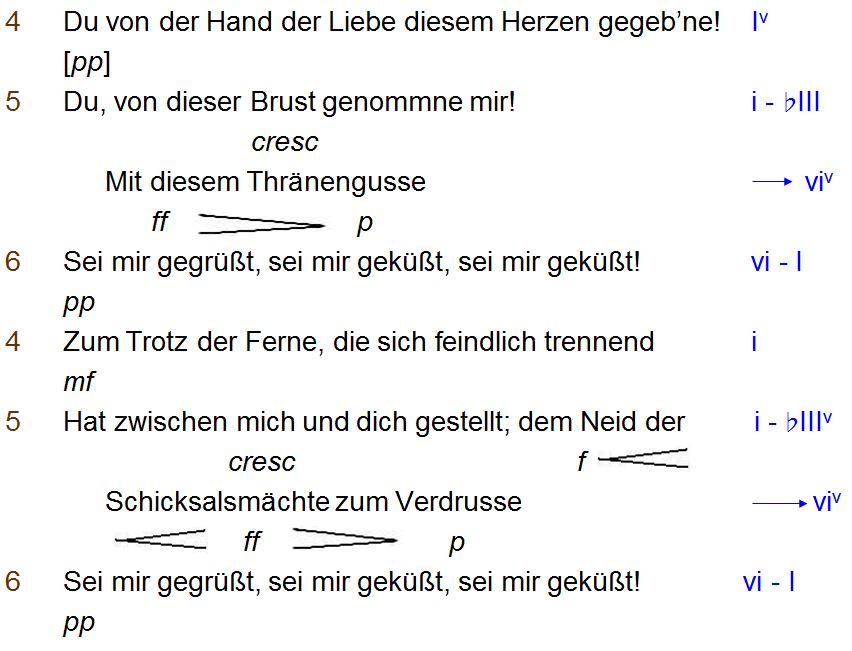

This subversion of the putative genre is continued in Schubert’s elisions of the second and third and then fourth and fifth stanzas, and the elisions within those stanzas, regrouping words to create two lines of text (and consequently two musical phrases) where Rückert implied three. The result is to create two six-line stanzas (subdivided into 2 three-line sections, each ending with the refrain) in place of the four quatrains.

Fig. 11: Schubert: Sei mir gegrüsst, D741. Outline of the phrase lengths, tonal structure and dynamics in the second stanza.

As we can see, one consequence is the further undermining of any regularity of phrase length: indeed in the second and fifth lines there is a sense of the text being barely accommodated in the musical phrase, in danger of completely breaking the mould, only to be partially contained and some equilibrium restored by the two-bar patterns of the refrain. Similarly the tonal range of this new stanza extends beyond that of the conventional opening, pushing against its implied boundaries in the second and fifth lines. My attention was drawn to all of this by Rehkemper’s daring handing of another aspect of the music – Schubert’s dynamics.

The basic dynamic level is pianissimo but with two fortissimi, in lines two and five. One notable feature is that whereas the crescendos into the dynamic climaxes have some space, the diminuendos are very rapid. All the performances I had heard before tended to underplay the fortissimos which, if nothing else, makes it easier to effect a convincing return to pianissmo for the refrain. Rehkemper, on the other hand, gives the fortissimos their full weight and darkens his voice: the effect is not merely to suggest erotic passion, but despair and anger. The fact that the transition back to the pianissimo of the refrain is abrupt heightens the sense that the dynamics too – and by implication the singer’s emotions – are scarcely contained.

Mus. ex. 2: Schubert, Sei mir gegrüsst, D741, bb. 29–59.

Herman Rehkemper (baritone), Manfred Gurlitt (piano), rec. 1928.

The process is taken further in the final stanza:

In the fifth line the music explores a new tonal area – the subdominant – before moving, via the most radical chromatic progression of the song, to the dominant of D flat major: this time the disruptive elements are not wholly contained: the piano, uniquely, has to provide linking dominant preparation for G minor before the singer can reiterate his containing refrain: it is as if, after the climax provoked by the imagined physical embrace, he has to stand back and take a deep breath to control himself. The intensity of Rehkemper’s utterance here – and one must admit he sustains the final ff longer than Schubert indicates – makes the struggle to regain composure almost palpable.

Mus. ex. 3: Schubert, Sei mir gegrüsst, D741, bb. 60–99.

Herman Rehkemper (baritone), Manfred Gurlitt (piano), rec. 1928.

I have discussed rather briefly only some of the aspects of the song that can be related to my understanding of what Rehkemper and Gurlitt are saying about and through the piece – for example nothing in detail about the melodic or harmonic processes, or about Schubert’s use of vocal range. The problem is that even if I had time to do so, and I have already spoken for longer than it takes to listen to the song, the real difficulty is showing, in words, how all these elements interact in a complex and coherent artistic object. Of course you may disagree with my way of hearing the performance, or may think that that I’m on to something, but that Rehkemper and Gurlitt have a perverse reading of the song. I can only respond that for me this is a performance of expressive intent, intellectual integrity, and one that has immeasurable enriched my understanding. Such insights are what performers give to the other communities in and beyond the Royal College of Music.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | All of the photographs reproduced here were taken and supplied by Lisa Philpott (University of Western Ontario Library) to whom I am most grateful. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Stephen McClatchie, ‘The 1889 version of Mahler’s First Symphony: a New Manuscript Source’, Nineteenth-Century Music XX/2 (Fall, 1996), 99–124 |

| ↑3 | Herbert Killian, Gustav Mahler in den Erinnerungen von Natalie Bauer-Lechner, revidierte und erweiterte Ausgabe (Hamburg: Karl Dieter Wagner, 1984), p. 173 |

| ↑4 | This interface has since been replaced by an entirely new and more flexible design. |

| ↑5 | For a .pdf of the song. edited by Eusebius Mandyczewski, click here. |

| ↑6 | Schubert: Memoirs by his Friends, collected and ed., O.E. Deutsch (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1958), 262. |